Love movies? Hate forming your own opinions? Well, you’re in luck, buddy, because here is GAMbIT’s list of the ten best films of the year.

Honorable Mentions: Black Panther, exactly the kind of game-changer that Marvel needs a decade into its box office supremacy, boasting one of the best villains that the MCU has ever seen; Paddington 2, a frothy antidote to malaise and vitriol in the age of Trump; Mission: Impossible – Fallout, a kinetic and wonderfully exhausting film that’s probably the best action movie since Mad Max: Fury Road, and shows why Tom Cruise is one of our last reliable movie stars; Three Identical Strangers, a documentary which I had some issues with from a filmmaking perspective, but which has a story so outlandish and engrossing that it truly does need to be seen to be believed; A Quiet Place, a slick, inventive thriller that makes us look at John Krasinski in a new light as a director; Incredibles 2, a zippy, feminist jolt of energy that examines the role of superheroes in the pop-culture zeitgeist, featuring a score by Michael Giacchino that is honestly Star Wars-level good; Unsane, a claustrophobic, psychosexual thriller for the #MeToo era, with one of the best scenes Steven Soderbergh has ever directed; A Star is Born, Bradley Cooper’s stunningly assured directorial debut, which is both a rousing film in its own right and the announcement of a major talent behind the camera

Movies I Haven’t Seen Yet Because This Has Been a Busy Year for Great Movies and I Don’t Get Screeners or Invites to Press Screenings and This Is An Unpaid Gig and I’m Doing the Best I Can, So Get Off My Back if None of These Appear on the List, ASSHOLES: Eighth Grade; Won’t You Be My Neighbor?; Madeline’s Madeline; The Tale; Isle of Dogs; Revenge; Leave No Trace; Blockers; The Death of Stalin; Blindspotting; Crazy Rich Asians; Support the Girls; Suspiria; The Favourite; Roma; First Man; If Beale Street Could Talk; Can You Ever Forgive Me?; Burning; Shoplifters; Widows

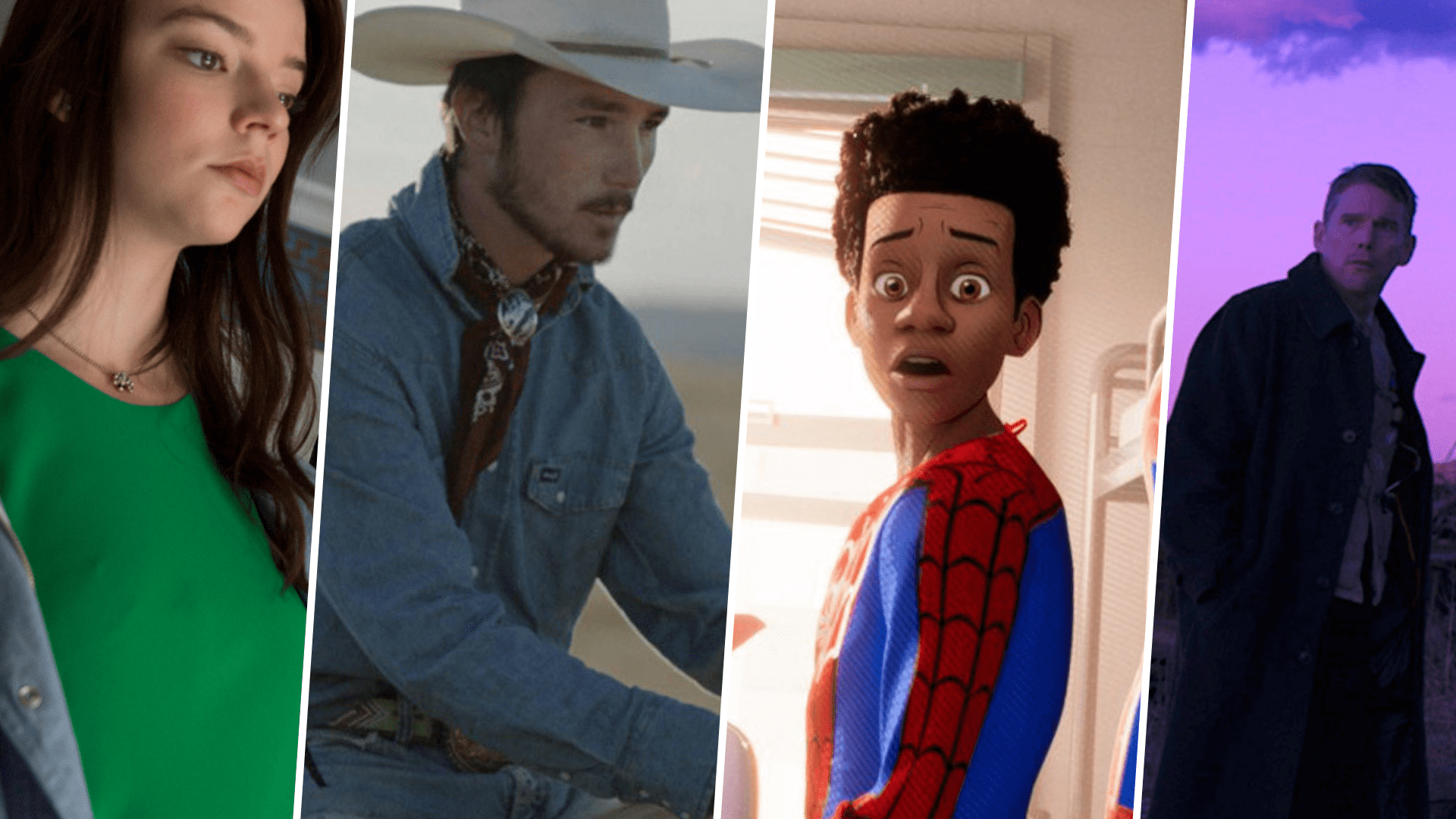

10. Thoroughbreds

Cory Finley’s film has been (somewhat inaccurately) likened to Heathers or American Psycho, but those comparisons do Thoroughbreds a disservice, as they ignore the underlying sweetness at the film’s core. Even though it follows two budding teenage sociopaths (Olivia Cooke and Anya Taylor-Joy) as they plot the murder of one of their stepfathers, Thoroughbreds is, at heart, a film about friendship, and the ways that the people you know will change your life, for good or ill. Cooke and Taylor-Joy are both fantastic in their roles.

Cooke is deadpan and grimly hilarious as a girl who by her own admission has no feelings. Taylor-Joy delivers a strong slow burn of a performance that shows there’s more to her character than her affluent, successful facade. Anton Yelchin, in his last film role, steals any scene he’s in, giving a surprisingly layered and nuanced portrayal of a wannabe drug kingpin. Thoroughbreds can be dark and cynical, but not for the sake of darkness and cynicism. It creates its own little world, which is occasionally cruel and repugnant, but always strangely inviting.

9. Hereditary

Ari Aster’s stunningly assured feature-film debut is one of the rare sensations to live up to the hype. Touted as “this generation’s Exorcist,” Hereditary took its rightful place alongside modern horror classics such as The Babadook and It Follows. The scares are quick and nasty, and Aster doesn’t rely on jump scares, but rather the intense, palpable sense of dread that his film cultivates. There is a wordless sequence in Hereditary that was so intense and upsetting that I nearly left the theater during it. Toni Collette delivers the best performance of her career: wounded, grieving, yet far from one-note, in her occasional bits of mania or nastiness. Alex Wolff matches her beat for beat, showing talent that can only come from an enormous emotional reservoir. Hereditary‘s ending has polarized viewers, but whatever your stance on it, the film is still as visceral and experiential as films can get. Here’s hoping that Aster is here to stay.

8. BlacKkKlansman

Spike Lee’s newest, and possibly greatest, film is so audacious and timely that if it weren’t a true story, it could only be invented by Lee; as a title screen says, it’s based on “some fo’ real, fo’ real shit.” It is a nakedly political film, hurled like a firebomb into the current political discourse (it even ends with a lengthy dedication to Heather Heyer, who was slain by a neo-Nazi during the Charlottesville riots of 2017). BlacKkKlansman is the story of a black cop, Ron Stallworth, who, along with another officer, infiltrated the Colorado Springs chapter of the KKK in the 1970s. Lee pours all of his anger, sorrow, righteousness, and indignation into the film, making it hilarious, upsetting, and horrifically topical, sometimes all in the same scene.

As Stallworth, John David Washington turns in a performance of effortless charisma and magnetism; as his partner, Flip Zimmerman, Adam Driver cements his standing as one of the essential actors of his generation. BlacKkKlansman is about race, identity, blackness, Americanism, the black experience in America, the police, black power, white power, and the soul of this country – in that sense, it is quintessential Spike Lee.

7. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse

How do you bring innovation to a genre that has long since reached the point of ubiquity? What else is there to say or show that desensitized audiences haven’t seen before? Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (from directors Bob Persichetti, Peter Ramsey, and Rodney Rothman) does more than breathe new life into a genre on the brink of staleness, it practically (and effortlessly) reinvents the genre itself. Few films in memory – indeed, few films ever – match Spider-Verse for its verve and panache, for the sheer kinetic spectacle that unfolds for 116 minutes.

For all of its innovation, its hilarity, its poignancy, Spider-Verse makes a case for a new approach to superhero films. Anchored by a stellar voice cast – including Shemar Moore, Jake Johnson, Hailee Steinfeld, and Liev Schreiber – the film shows us that anyone can be a hero. Anyone can be Spider-Man, because in this case anyone is, be it a sentient pig or a young girl psychically bonded to a machine. There was nothing like Spider-Man on screens this year. It’s a film with the kind of breathtaking ingenuity that leaves you awestruck, and a little happier that this medium exists.

6. Sorry to Bother You

Rapper and activist Boots Riley’s first foray into filmmaking is like a Day-Glo pipe bomb: wild and unpredictable, pastel colors masking the anger and bitterness at its core. Stylistically, there was nothing like it this year, and it seems more at home alongside the consumerist satire of the 1980s, films like Robocop, They Live, and Repo Man. Riley goes for the jugular, crafting a cinematic “fuck you” to corporations that pretend to be our friends. Capitalism dehumanizes people; in Sorry to Bother You, it literally turns them into monsters, people who, as the title suggests, are forced to apologize for their own existences.

Riley directs with the surety of an old hand; at times it’s hard to believe that this is his first time behind the camera, so effortlessly does he coax magnificent performances out of Lakeith Stanfield, Tessa Thompson, Steven Yuen, and Armie Hammer. For all of its strangeness, for all of its attitude, Sorry to Bother You is one of the most earnest films of the year. It yearns for a world where people just treat each other fairly.

5. You Were Never Really Here

Lynne Ramsay (We Need to Talk About Kevin) adapted Jonathan Ames’ novel, and in doing so she created a work of startling, breathtaking intensity. The film is anchored by a never-better Joaquin Phoenix as Joe, a moody, sensitive, brutal enforcer who specializes in the retrieval of lost girls (think Liam Neeson in Taken, but burdened by existential angst). Joe lives with his mother, and adheres to a moral code, and when he clashes with people who don’t abide by the same code, the results are both explosively violent and strangely poetic. YWNRH is many things: a tense, psychological thriller; a study in, and interrogation of, masculinity; and a surprisingly moving story of love and redemption.

4. The Ballad of Buster Scruggs

The eighteenth film from the Coen brothers shows the best filmmaking duo since Powell & Pressburger firing on all cylinders. Buster Scruggs shows the brothers’ effortless affinity for genre, and their mastery of the short film. Their anthology is as funny as it is devastating; in the title segment, Tim Blake Nelson plays Bugs Bunny by way of Peckinpah, and in “Meal Ticket,” Liam Neeson turns in the darkest performance of his career, and does it with hardly saying a word.

The Coens have often been accused of being cynical or nihilistic, and here they embrace both descriptions, while also turning in some of the most humane work of their career; to wit, Tom Waits delivers an Oscar-worthy performance in “All Gold Canyon,” embodying the sorrow, solitude, and optimism that drove men out west to pan for gold. Any of these short films would be contenders for the Oscar in that category. That The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is made of the remnants of the Coens’ Netflix series just shows how easy this is for them – or at least how easy they make it look. They are not, by trade, short film makers. But here they prove their mastery of it.

3. Annihilation

After writing 28 Days Later, and directing 2015’s Ex Machina, Alex Garland has quietly been redefining the modern science-fiction movie. Annihilation is his masterpiece. Garland’s film is a dreamlike meditation on loss, depression, and grief, buoyed by a solid Natalie Portman and some of the year’s best visuals. The world of Annihilation is beautiful and terrifying, full of flora and fauna that are sometimes one and the same. (And you will not forget the bear scene.) Annihilation has the kind of audacious, go-for-broke ending that is designed to be discussed and analyzed, and the beauty, and brilliance, of Garland’s execution is that it leaves room for multiple interpretations. Annihilation is the kind of movie that reminds us of why we go to the movies in the first place.

2. The Rider

Chloe Zhao’s second full-length film is a stunning achievement, an essential investigation of American masculinity and this country’s heartland that brings to mind films like The Wrestler or Unforgiven. Brady Jandreau plays a version of himself named Brady Blackburn, a rodeo cowboy who received a head wound from a horse and can now longer ride. The Rider is a (barely) fictionalized version of Jandreau’s story. He suffered the same injury, and to add to the film’s verisimilitude, Zhao uses a cast of almost all non-actors, even going so far as to cast Jandreau’s father and sister to fill the same roles in her film. It’s a risky gambit (just ask Clint Eastwood, whose The 15:17 to Paris drew jeers earlier this year) but it pays off enormously.

Jandreau gives a remarkably assured performance in his film debut, laconic but also guileless. He just wants to ride horses, and now he can’t. Through the character of Brady Blackburn, Zhao examines American masculinity through one of its most recognizable avatars: the cowboy. Both versions of Brady have to find their place in this suddenly new world. The Rider is achingly intimate and heart-wrenching; it achieves a sense of pure poetry in scenes where Brady trains horses. Picturesque, elegiac, and boasting two of the most emotionally ravaging scenes in recent memory, The Rider is nothing short of a masterpiece.

1. First Reformed

The men in Paul Schrader’s films – like Blue Collar, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, or Taxi Driver (which he wrote) – find themselves at odds, or in outright rebellion against, their times and cultures. That’s certainly the case with First Reformed, Schrader’s finest film, in which Ethan Hawke’s Reverend Toller doesn’t so much rebel against the world as much as he finds himself realizing just how much it’s changing under his feet. Religious dogma exists in a kind of stasis, but Toller, after meeting a radical environmentalist, finds himself grappling with a timely existential question: “Can God ever forgive us for what we’ve done to His creation?” Schrader’s film does not hector or moralize. It is not proscriptive, and it offers no easy answers.

Through Toller’s crisis of faith, it merely asks us to consider the damage we have wrought on the planet. First Reformed doesn’t admonish us to change before it’s too late; it instead gives a dire warning that it might be too late already. It describes a small-scale apocalypse, in which the end of the world is upon is. Ethan Hawke is the best he’s ever been: stoic and removed at first, yet still magnetic. He only raises his voice a few times, and when he pleads with a fellow clergyman, “We have to do something!” you can hear the desperation and terror in his voice. The film’s ending – one of the most bracing and jaw-dropping of the year – hearkens back to John Huston’s Wise Blood, but still belongs unmistakably in Schrader’s film. First Reformed is the best film of 2018, and it’s not even close.