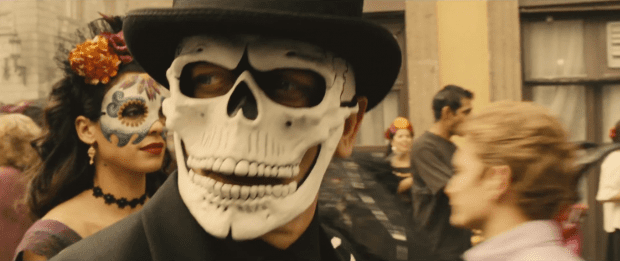

Spectre, the 24th installment in the immortal James Bond franchise, opens so unbelievably strong that it’s almost inevitable that the rest of the film will falter in comparison. Opening at Mexico’s Dia de los Muertes celebration, the camera follows a skull-clad Bond (Daniel Craig) in a fluid, unbroken shot involving stairways, elevators, balconies, and hundreds of extras, as Bond and an unnamed beauty retreat to a hotel where Bond immediately doffs his skeleton suit, revealing another suit underneath it, in a sly sight gag. Skyfall‘s Roger Deakins is out as DP, replaced by Interstellar‘s Hoyte van Hoytema, who acquits himself nicely here. Sam Mendes, the Oscar-winning American Beauty director who also helmed Skyfall, uses a muted color palette that makes everything look dusty and nearly ethereal, as if the moral haze of Bond’s life has been made tangible. All these factors – plus Craig’s now-perfected steel-eyed squint – combine to make a bravura opening that doesn’t even bother to culminate with the collapse of a building; no, it adds on a foot chase and a fistfight inside a crashing helicopter.

Is it any wonder, then, that Spectre has trouble living up to the promise of those first brilliant minutes? The fundamental problem with the film – which is nevertheless enjoyable, although it could have used a heavier hand in the editing room – is that it is of two minds. On the one hand, it would serve as a fine farewell to Craig’s moody, emotionally dead incarnation of Bond. On the other hand, Spectre in many ways serves as a 150-minute introduction to a new nemesis for Bond, which wouldn’t make much sense if Craig wasn’t returning. So it with this schizophrenic mindset that Spectre unfurls.

The film follows Bond as he investigates the titular organization and its mysterious leader, Franz Oberhauser (Christoph Waltz, not chewing as much scenery as one would think). It’s a good thing that Spectre ditches Bond author Ian Fleming’s original campy acronym – Special Executive for Counter-intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge, and Extortion – because so much of the film borders on self-serious camp as it is. It’s almost a shock to see a mute henchman (Dave Bautista) with metal thumbnails, especially after the relative straightforwardness of Skyfall, but then one remembers that the villain in Casino Royale cried tears of blood, and Skyfall starts to look more and more like an anomaly.

(Sorry to keep bringing up Skyfall, but it’s very likely that it’s the best Bond movie ever made, and as it shares a director with Spectre, the comparisons are inevitable.)

Elsewhere, M (a returning Ralph Fiennes, wonderful) grapples with tech guru C (Sherlock‘s Andrew Scott), who wants to implement a worldwide surveillance network. Spectre‘s critique of the twenty-first century’s surveillance state is a little too on the nose to be truly effective, and doesn’t raise any new arguments about the thorny issue. It’s also borderline ironic, considering the setting: London has a population of 8.5 million and utilizes 20% of the world’s CCTV cameras, so if any objection to surveillance is going to come up, it’s unlikely to stem from any branch of the British government. Regardless this subplot does put Fiennes and Scott in the room together, and it’s fun to watch their polite facades crumble.

Craig and Waltz, however, don’t fare as well. Waltz is a fine actor – the man has two Oscars – but his scenes with Craig lack the kinetic, latently homoerotic tension of Craig’s scenes with Skyfall heavy Javier Bardem. Waltz’s role is clearly meant to continue, and it will be great to see him grow into the character of Oberhauser, who already benefits from Waltz’s subtle theatrics: no one else could convincingly purr out a line like “Me: the author of all your pain.”

Spectre has a long memory, but unfortunately it asks that the viewer does as well. The latest Bond girl (not Monica Bellucci, as the hoopla would have you believe; she’s in the film for about ten minutes) is Madeleine Swan, played by Blue is the Warmest Color‘s Lea Seydoux, who seems to grow more beautiful in every scene she’s in. Swan is the daughter of Mr. White, who – oh wait, you don’t remember Mr. White? No, of course you don’t, because he was a minor villain in Quantum of Solace, the worst installment of the Daniel Craig Bond films. At one point Bond picks up a VHS titled “Vesper Lind Interrogation,” and not only is it banking on us remembering Eva Green’s character from Casino Royale, but it misspells her name, which is Lynd, not Lind. I will allow that the misspelling could have been a mistake on the author’s part, not the film’s, but it’s an easy fix that wouldn’t make viewers ask these kinds of questions. Also, from a narrative standpoint, don’t tease us with a Jeffrey Wright appearance and then not show us Jeffrey Wright. That’s filmmaking 101.

All those complaints notwithstanding, Spectre is definitely not a failure. Sam Mendes has grown more comfortable in the director’s chair; a theater director by origin, Mendes has a truly enviable sense of spatial command that adds fluidity and urgency to fight scenes, of which Spectre has about fifty, the best being a throwdown on a train between Bond and Bautista’s Mr. Hinx, setting which makes for a nice retro throwback. The ambition and scope on display is impressive, and the callbacks to previous villains like Casino Royale‘s Le Chiffre, Quantum‘s Greene, and Skyfall‘s Silva is a good attempt at world-building. Spectre‘s main failure is in reaching too far at once; the film tries to have as many arms as the octopus which serves as Spectre’s insignia, and coming on the heels of a classic like Skyfall, the only Bond film that could have been a Best Picture contender at the Oscars, it’s going to be noticeable when one of those arms loses its grasp.