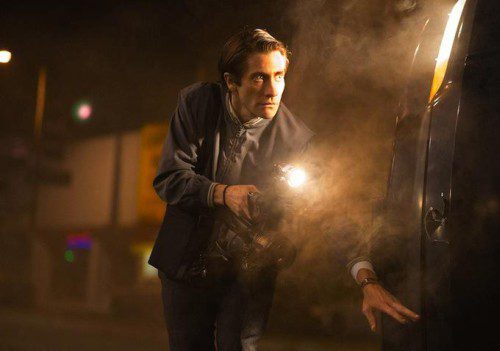

As Louis Bloom, Jake Gyllenhaal plays a newcomer to the business of shooting sensational pieces and selling them to the local news networks in what might be his most memorable role to date. His character excels at the job for a very simple reason: there’s nothing else to him except the thirst for success. Boundaries aren’t something he recognizes or respects. He’ll photograph victims bleeding in ambulance stretchers, clinically recording the most gruesome details with absolutely no thought of good taste or common decency. He won’t hesitate either to break into homes or tamper with crime scenes to get the perfect shot. He’ll screw over competitors too. For him everything is about beating the other guy to the same story. Bloom’s all ambition, nearly no humanity, like a cross between Daniel Plainview and Nicole Kidman’s ruthless anchor from To Die For.

Precious little is revealed about him in Nightcrawler, the directorial debut of screenwriter Dan Gilroy. There is nothing like a backstory–only a couple scraps of details offered about himself which may or may not be true. When the movie starts we find him trespassing on a construction site and getting caught (he’s in the process of stealing parts). When he can’t con his way out, he pummels the security guard to the ground and flees the scene. Afterwards when the person he sells to won’t hire him on a permanent basis (not employing verified thieves usually a sound policy), he wanders off a loner in need of a job.

It’s only by a chance freeway side encounter of a burning car wreck and the freelance cameraman who shows up to tape it (he’s played by Bill Paxton) that he strikes on the idea of going into that field. With money he gets at the pawn shop off of presumably stolen stuff, he arms himself with a rather primitive handheld camera that makes people look at him suspiciously and others in the trade scoff. The beginning for him is humble, but once he starts selling footage to Nina, the news director at a local station (Rene Russo), he rapidly becomes a force to be reckoned with.

If this is a character study, it’s one absent a character to study–or at least one who changes in any meaningful sense. By the last frame in Nightcrawler Louis Bloom is the same blank yet charismatic and creepily enigmatic man he was at the start. Scenes without another character find him strikingly, excessively alone like Travis Bickle. Dealing with others he speaks in purely financial and factual terms, like when proposes a relationship on his first date with Nina and then quickly switches into a full-scale economic threat when she doesn’t consent that viciously yet calmly plays on her weaknesses.He hires an assistant (Riz Ahmed) who shows up to the interview unaware of what the position is, he’s just so desperately in need of income but mostly gets saddled with big demands and lectures about what it takes to be a top employee in a tough job market. In his presence Bloom never drops the strict professional facade, though at one point he intriguingly offers that the problem might be less that doesn’t understand people, and more that he just flat out dislikes them.

Gilroy clearly intends this though to be taken mainly as a provocative media satire. The neat trick about that is that because of Gilroy’s stark competence and dead of Los Angeles night nourish vibe that calls to mind Drive, it also plays like a thriller that’s willing to stoop nearly as low as its subject. Right down to the sinisterly winking last scene, the tone is of the blackest comedy. It’s a sick joke that goes dismally flat, and quick. Gilroy shows considerable proficiency at the mechanics of the filmmaking itself, but his repetitive script blatantly passes on chances to dig into this character and instead wastes too much time on unedifying arguments between him and his assistant about pay and his work performance and the pacing sometimes falls off, particularly in the middle stretches.

Nightcrawler can be shockingly ugly and cynical. But even as a send-up of the unrelenting news cycle and the local producers eagerly willing to exploit fears of urban crime committed against the white middle classic, it’s beyond belief that any sane person would even for a split second broadcast some of the extremely questionable footage Bloom brings in (satire has to have at least a shred of plausibility to persuasively indict). The last act just goes bonkers with entirely unbelievable events stacking up and eliciting more dread than entertainment value along the way. Gilroy doesn’t find the right tone to make this all work as compellingly as he intends. What he rubs our noses in horrifies a couple times, but not with truth it unveils like Sidney Lumet’s classic and timeless Network did or even Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers. In any case, he doesn’t actually tell us anything we didn’t already know or suspect.

It’s up to Gyllenhaal to do that and fortunately he makes it into something of a triumph. Stepping into the part of a callous sociopath wouldn’t seem like a natural fit for the actor, consistently good and sometimes great in a number of roles but not as exquisitely icky as this one (for all his talent he can be miscast, like in last year’s Prisoners). But the nearly thirty pounds he shed to play Lewis Bloom make his moon-like eyes somehow seem even bigger and twitchier. Everything about him is more wired and intense, right down to his combed back hair which makes his stare seem downright murderous.

The role is a mordant riff on obsession and derangement and where the movie lays everything on thick and finds diminishing returns, Gyllenhaal is hilarious and has real chemistry with a terrific (and older) Russo. He’s a monster, but the worst and most insidious kind: one who is smart, driven, cunningly manipulative, and very, very good at what he does. He’s the kind of creep you could see yourself possibly crossing paths with one day or-most terrifying of all-working for.