“For me the movies are like machines that generate empathy,” Roger Ebert once described the way cinema brings incredibly diverse types of people together to experience things outside of their own lives. Those are the words we hear when Life Itself begins and you can nearly forget just how familiar and comforting his voice was. It’s great to hear it again. There are many who feel such a strong draw to the movies, but few understood why it is they feel that enthusiasm and awe as deeply as Ebert.

Too many critics make a fetish out of acting snarky and dismissive; being populist is surely a dirty word. Ebert became then the most known and respected mainstream critic in America by doing something vital and unorthodox: truly liking movies and people. For as much grief as he received in some corners for panning popular films like Blue Velvet and A Clockwork Orange, his default stance seemed to be vast appreciation for what the cinema had to offer. The enthusiasm in his writing was both inspiring and telling.

It was cancer that consumed so much of his time and energy in his later years until his death in April of 2013, but part of the immense warmth and joy of Life Itself, based on his memoirs, is seeing once again how that did nothing to shake his profound humanity or the love he had for Chaz. She was the woman who, as he saw it, saved him from growing old alone. The two met at an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and though she never thought she’d date a white guy-particularly one who weighed some 300 pounds-they did and married when he was 50 years old. “He didn’t care, he thought he was great. And that was so sexy,” she says of how he didn’t let his appearance have any effect on his confidence. Good call. Roger never had any children of his own, but the kids and grandkids that Chaz had he eagerly adopted as family.

Life before he met Chaz was marked by many professional highs (and a personal low or two), all which is documented here. Raised an only child in an all-American Midwest home (the Midwest truly is the most quintessentially American of all regions), he started writing for a newspaper full-time when he was only 15 (“I can write. Always could. On the other hand, I failed French five times”, he recalls). Harvard was out of the question financially, so he attended University of Illinois instead, editing the college newspaper. While a doctoral student at University of Chicago in need of a job he started working at the Chicago Sun-Times. Incredibly the position of film critic was essentially handed to him within months and he would write for the paper, although occasionally interrupted by medical problems and long hospital stays, from 1967 until his passing.

Much of the rest of his bio is fairly well known to those who read his columns or watched him on television. He became the first person to win a Pulitzer Prize for film criticism in 1975. Around the same time he was paired up with rival reviewer Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune for a public access television show. The idea of having two questionably dressed non-celebrities talk extensively about movies was quite nutty but on so many levels it worked and became a much bigger deal in the mid-80s when it was syndicated and aired nationally. Richard Corliss, the critic for Time, puts his finger on it when he says the two became “like sitcom characters in that theater.” It’s not that the formula wasn’t controversial: many bristled at the idea that a judgment on a film could be boiled down to a simple thumb up or down—or that critics should be so friendly with filmmakers, it’s that the public at large didn’t mind. “Two thumbs up” from Siskel & Ebert became one of the best selling pitches for Hollywood movies.

In more revealing anecdotes, we learn from close friends back in Chicago that he had “the worst taste in women”, which included ladies for hire. He fared even worse with the liquor as a heavy drinking depressive (he quit cold turkey in 1979, back when the show was still quite young). The behind the camera sniping with Siskel that the public didn’t know about is brutally hilarious (they had enough mutual respect to seriously spar both as critics and people). The two often attended the same screenings with nary a word spoken to each other. When it came to business matters, even the order of their names in the show was a sore spot. For all the things revealed about the way they grew to seriously love each other and how Siskel’s death from brain cancer at 53 weighed heavily on Ebert, the most indelible image might just be a young Gene Siskel sporting a handlebar moustache next to a topless woman at some decadent party in the 70s.

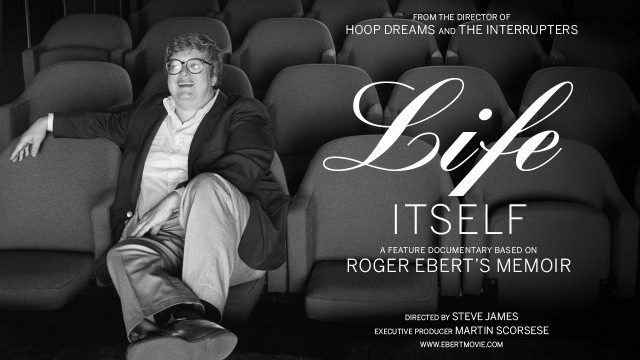

Directed by Steven James, who made the rousing classic Hoop Dreams (which Ebert named the best film of the 1990s), this is-fittingly for being about a critic-a terrific movie. It is an uncommonly engaging and colorful documentary; reverential in its way without ever feeling like some fluff piece. The presentation is unpretentious and uncluttered. The interviews are interesting and lack anything unnecessary or extraneous; the video clips and pictures are never dull. Production began when he was still alive. Intercut through the doc is the present reality of him, rendered voiceless when his jawbone was removed. The image of him hospitalized is somewhat shocking at first, but these moments with him are lovely. You can see the spirit of the man who wrote so beautifully and honestly about how he knew death was near, how precious life is, and how ready he was to say goodbye to it when that time comes. There’s also some good moments with Chaz like when she finds the standard-issue hospital Bible and says to him, “I take it this is not yours?”.

Life Itself is incredibly rounded in the way it captures Roger’s joy and his genius. As the experience of hosting a show about it made clear, trying to convince another person of your opinion is a maddening and often fruitless endeavor–even for the proud recipient of a Pulitzer Prize. He proved one could be a smart reviewer without being a cynic and how you could show piercing understanding of things beyond plot mechanics and lighting. He did that all while rapidly writing critiques (we learn that he could crank some of them out in thirty minutes) it in what A.O. Scott of The New York Times calls “that plain spoken Midwestern style”.

One of the most touching things in the movie is hearing from filmmakers who are forever grateful for the exposure his reviews gave them. Errol Morris, who became best known for The Thin Blue Line and The Fog of War, believes he wouldn’t have a career if not for the enthusiastic reception his debut Gates of Heaven received from raves on the show by both Siskel and Ebert. Getting Ebert to see your movie, for an upcoming director, was both an honor and a chance to make your work known to vaster audiences than would likely be reached otherwise. Film criticism is necessary and valid journalism than can enhance the discourse and the way we look at movies, even if so much of it falls so frustratingly short. Life Itself brings Roger Ebert’s decency and irreplaceable brilliance into full view, showing you what film critics at their very best-and life lived to its fullest-can be. Big thumbs up.