In its two decades so far, Pixar has given us many wonderful movies, starting with their first and to this date best, Toy Story. That 1995 game-changer set the bar at nearly impossible heights, sure, but more recent titles like Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, and WALL-E don’t just stand out as exceptional pictures geared towards children or first-rate animation, they were quite arguably some of the best films to come out in the mid-2000s period. Pixar has fairly consistently dazzled us with their innovative 3-D computer animation and they have told many terrific and clever stories in the process (extraordinarily managing to make us feel for toys, robots, rats, and for some viewers, cars too). What they haven’t done until now is making a movie that is quite as humane and life-affirming as Pete Docter’s Inside Out. It isn’t content to just be a knowing and sweet story about being a kid or a funny-smart exploration of the mind. This goes into new psychological terrain for animation and gives us something unexpected: a triumph of empathetic film making.

The mind being mapped out and explained belongs to Riley, a pleasant, well-adjusted 11 year old girl who is quite happy with her life until her dad’s work moves them from home in Minnesota to San Francisco. The move would feel like a stark change arriving from nearly anywhere in the country, but for a Midwesterner who lives for hockey and doesn’t know anyone in the city, it’s a strange, unwelcoming world where even the pizza is foreign and her drab new house is no comfort. Her first day at school she’s invited by the teacher to introduced herself to the class and midway through something suddenly goes terribly wrong. She chokes up from seemingly out of nowhere and feels an intense longing for the place she left. Given that she’s a preteen, the emotions hit even harder and her bad vibe continues. At home she’s no longer the sweet little girl, instead picking fights with her parents (voiced by Kyle MacLachlan and Diane Lane)–which of course is as confusing to them as it is to her.

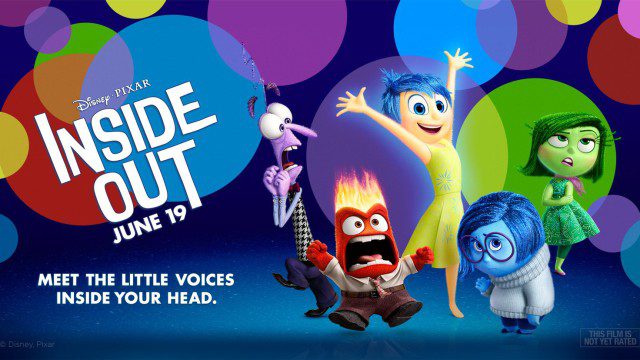

Inside Out is about all the seemingly inexplicable things constantly happening in all of our heads, but especially the overactive, developing minds of kids as they segue into adolescence. Docter, who wrote the screenplay with Meg LeFauve and Josh Cooley, cuts back and forth between the story as it unfolds and the mini-personalities in her head that sometimes-cooperate, sometimes-clash, giving the latter the lion’s share of the screen time. There’s Joy (a blue pixie-haired Tinker bell dead-ringer sunnily voiced by Amy Poehler), Anger (appropriately fury-red and voiced by Lewis Black), Fear (he’s Bill Hader), Disgust (giving the role to Mindy Kaling was a brilliant move), and Sadness (the glass half-empty Eeyore of the group with round glasses and a turtleneck sweater that make her seem even more downbeat, voiced by Phyllis Smith).

Perched in a command center like the Enterprise has in Star Trek, the emotions control what Riley does as they watch everything unfold on a big screen. They also take the fresh memories that are generated every day, sending them either to the personality islands for the core memories or to be stored long-term (they take the shape of little colored balls and are fired up chutes like a Willy Wonka factory of the cerebrum). When Joy tries to constrain Sadness from tampering with and thus permanently ruining any more of the memories, the two are sucked into one of the chutes and stranded out in Riley’s subconscious. It leaves Fear, Disgust, and Anger arguing over control at the worst possible time and a scary possibility that Joy and Sadness might be lost forever.

Docter, who previously directed Monsters, Inc. and the delightful Up, orchestrates many fantastically imaginative sequences along the way. This is a movie that truly has all the effusively witty and exuberantly creative energy of Pixar at its best, while still being charmingly silly enough to throw in a goofy throwaway Chinatown reference for the adults. In one scene that feels positively trippy, Sadness and Joy along with Riley’s one-time imaginary friend (he’s a part elephant, part cat creature who cries candy, voiced by Richard Kind) are nearly stamped out of her head altogether by stepping in the wrong chamber. They’re rendered into Picasso abstract art as they deconstruct before being reduced to nothing more than single colors. Inevitably a picture that grapples with what constitutes consciousness would have to tackle dreams and here it offers up probably the most deliriously brilliant scene when Sadness and Joy sneak into the dream production theater where actors reenact events from the day (hilariously a goateed dude reads off the script to play Riley, doing a weird impression of her voice) in an attempt to disrupt and thus wake her up. It goes into truly surreal places. With it Docter nails the weird logic and rhythm of our dreams, a part of being alive that takes up maybe a third of our time on earth yet remains such a head scratching mystery.

The joy and immense warmth of Inside Out is how it’s not just concerned with the forces in Riley’s head but how we’re all more complex creatures than we seem, constantly absorbing and being shaped by life as it happens. An argument at dinner between Riley and her parents cuts to the mom’s own internal operations, deeply concerned about the sudden changes in her daughter–while also still fantasizing a wee bit about a hunky Brazilian pilot she once dated. For his part the dad’s emotions have their command screens all tuned to sports and barely fumbles together a response. Paying attention or not, he’d still be justifiably perplexed by his daughter’s behavior. It suggests we could all afford to be a little bit more understanding about all the ways the workings of another person’s mind can often elude and frustrate us. The movie gets the formula right too many get so dreadfully wrong: stimulating and complex more in ideas than plot structure. The story construction itself is surprisingly simple and sturdy even as it dizzyingly packs on so many great jokes and concepts. Because of, not despite that, the emotions are fully realized and eventually overwhelming. Inside Out, one of the year’s best movies, earns every single one of its sneakily disarming tears.