The History Channel’s Houdini is fraught with exposition, stuck with a generic, anachronistic score, and laden with cheesy flashbacks (not to mention editing straight from the CSI school of learning), but for its faults it’s still entertaining as hell – just like the man himself. There’s an old adage about magic: It’s not about tricking people, it’s about making people believe, and Houdini, buoyed by a great performance from Adrien Brody, embodies that maxim nicely. To an extent, we are still as captivated by Harry Houdini today as we were back in the early 1900s, and as the film points out (several times), it might be because we’re all looking to escape from something. Death is the ultimate inevitable, the great equalizer, and possibly the most frightening aspect of all of our lives. To see someone like Houdini routinely spit in its face was a great thrill for audiences back then, and that feeling translates pretty well to film.

Harry Houdini was born Erich Weiss, a German-speaking Jew from Budapest. He and his family moved to Appleton, WI, where his father was the local rabbi, in spite of the fact that he never learned to speak English. When Erich (who I’ll call Houdini from here on, because duh) is called on stage to aid a magician, he decides his future almost on the spot. The time spent in Houdini’s youth moves a little too quickly, and Brody is saddled with the unfortunate task of explaining every single thing that happened, things that could have been better conveyed through dialogue or even an askance look. Louis Mertens does good work as the young Houdini, and his wide-eyed enthusiasm is infectious.

As an adult, Houdini is performing with his brother Dash (Tom Benedict Knight), before unceremoniously booting him from the bill so he can team up with the new Mrs. Houdini, a young dancer named Bess (Kristen Connolly, Cabin in the Woods). It would have been nice if Houdini let us see Dash being fired, but this movie ain’t about him, as it continually reminds us. Houdini adds Jim Collins (Evan Jones, 8-Mile) to his team, and sets out to conquer the world.

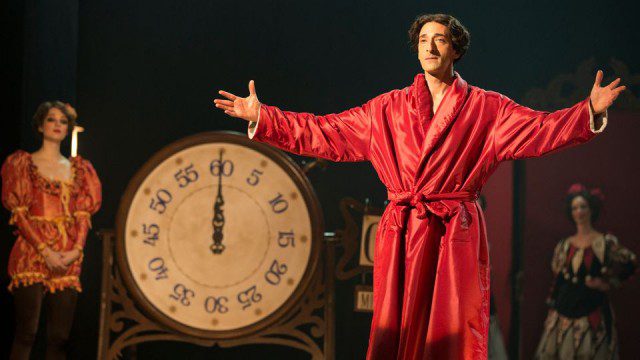

One of Houdini‘s greatest strengths lies in its presentation of Houdini’s performances. His escapes are genuinely thrilling, even the failed ones, like when he gets trapped in a Chinese Water Torture chamber and has to be hacked out with an axe. “Fantastic!” he gasps, and the relief is palpable. Brody commands a room no matter the size, be it the Adelphi Theater in London or a private audience with the Romanovs and Rasputin (this is possibly the best scene of the night). These scenes do what magic is supposed to do – they make you smile, gasp, worry, and ultimately applaud. Director Uli Edel (The Baader Meinhof Complex) is clearly in his element here; it’s in the personal scenes between Houdini and Jim or Bess that he stumbles.

Arguments seem to come out of nowhere; the film covers a long period of time (about the first twenty years of Houdini’s career), but gives no hint as to the origin of any marital strife with Bess. Conflict arises because the script needs it to, and although Brody and Connolly have nice chemistry together, the narrative isn’t doing them any favors, and Houdini sags as a result. Moreover, sometimes Houdini is charmingly cocky, with a winsome, lopsided smile, and in other parts he’s an egotistical jerk, drunkenly telling Bess that she’s the “wife of the great Harry Houdini!”

It gets a shot of life in the second act, as Houdini is recruited by the Secret Service and MI-5 to spy on Kaiser Wilhelm while he’s on his tour of Europe. Brody – and Houdini – clearly relishes the chance to do something new, and Houdini really perks up during any of these scenes.

Houdini ends with a bit of a whimper, as it seems in a rush to get to the finish line. A plot about Houdini’s popularity being usurped by movies seems tacked-on, and even though the story is nothing new, it still has merit, and is a huge deal to Houdini, just not so much to the audience.

Obviously, the first part of any story should set up the second, but the first half of Houdini leaves the audience wanting more. Which, now that I think about it, is just what magic is supposed to do.