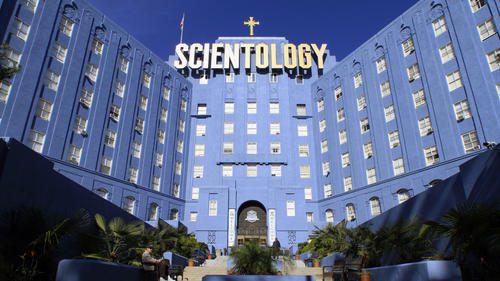

After films like Taxi to the Dark Side, Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room, and The Armstrong Lie, Alex Gibney was already on his way to cementing his status as the century’s most important documentary filmmaker. With Going Clear: Scientology & the Prison of Belief, the argument becomes ironclad. Based on Pulitzer Prize winner Lawrence Wright’s pipe-bomb expose of the same name, HBO’s incendiary documentary raises the curtain on one of the most secretive organizations on the planet. The film is never less than riveting, and at times genuinely unsettling.

Going Clear takes a two-pronged approach to its narrative. The first half of the film – the entirety of which is excellently edited by Alex Grieve – is devoted to biographical material about Scientology’s founder L. Ron Hubbard. In spite of his elusive persona, Hubbard is remarkably forthcoming in interviews, and while Going Clear is never tawdry enough to be called a hatchet job (Scientology does a good enough job of slandering itself), Hubbard still comes off like the consummate con man, his tobacco-stained teeth stretching into a huckster’s rictus.

The strange thing is, Going Clear never paints Hubbard explicitly as a villain. Wright himself is surprisingly sympathetic towards the man, saying that despite its dubious origins, Scientology presented a potential escape for Hubbard from his personal demons (despite Scientology’s famous objections to psychology, Hubbard formally requested psychiatric help from the Veterans Affairs Department). If there is a villain in Going Clear, it is unmistakably David Miscavige, Hubbard’s viciously ambitions successor and current head of the church. Miscavige’s movie star good looks do little to disguise the menace that he exudes with his very presence. Several prominent defectors from Scientology – Marty Rathbun, Spanky Taylor, Mike Rinder, Oscar winner Paul Haggis – readily offer testimony of Miscavige’s pattern of bullying and abuse.

The latter half of Going Clear, where it seamlessly transitions from biography to expose, is where the film really bares its teeth. It’s damning enough that ex-Scientologists identify as “defectors” and reference their “escapes,” but as much as the church – and I use that word reluctantly – would like you to believe that these men and women are liars, drunks, and malcontents, the fact remains that their testimony is startlingly selfless, considering the amount of harassment and abuse that they’ve gone through since leaving the church and being branded as SPs (“suppressive persons”).

But Scientology is nothing if not the religion of celebrities, and Going Clear goes to great lengths to show the appeal of the church to men and women who trade money (which they have in abundance) for preferential treatment and a financially attainable path to enlightenment. Gibney’s film takes aim at John Travolta and Tom Cruise, the church’s most high-profile members and its most vocal proponents. While Going Clear doesn’t condemn their involvement – interview clips of Travolta are presented in a straightforward fashion, while Cruise’s viral Scientology pep talk speaks for its own crazy self – it does take them to task (Cruise especially) for not speaking out against Scientology’s systemic abuse and corruption. Which is not an unfair argument to make: why haven’t Cruise and Travolta addressed the issue at all?

The most impressive feat that Going Clear accomplishes is its even-handedness. Scientology is very easy to attack, from its bizarre mythology, involving Xenu and alien souls, to its pattern of misinformation and disingenuousness, but Gibney is wise enough to let his interview subjects present the facts in unvarnished, bald-faced confessions. (Actor Jason Beghe puts it in stark terms: “Every Scientologist is full of shit.”) The film’s subtitle, The Prison of Belief, becomes more and more apt during Going Clear‘s two-hour runtime. It’s a deeply insidious, disconcerting film that sheds light on one of the stranger facets of faith in the twenty-first century.

The only criticism I have about this brilliant, essential film is: who will it convert? Critics of Scientology are just as set in their dogmatic belief as are adherents to Hubbard’s teachings, so in the long run, Going Clear is unlikely to change many minds, regardless of how expertly it lays bare the church’s brutality and fascism. That notwithstanding, it should be required viewing in any discussion about the dangers of blind belief.