A father uses digital art to share his family’s story, giving players an interactive space to grieve, empathize and hope

Ryan and Amy Green faced every parent’s worst nightmare when their infant son Joel was diagnosed with brain cancer. But Ryan, an independent video game developer, imagined that something larger and brighter could come out of his family’s struggle: a poetic video game that would help him share an experience so rarely discussed—raising a child with cancer. Their heroic and life-affirming story is documented in Thank You for Playing, an Official Selection of the 2015 Tribeca Film Festival, which will premiere during the 29th season of the PBS series POV (Point of View) on Monday, Oct. 24, 2016 at 10 p.m. (check local listings). American television’s longest-running independent documentary series, POV is the recipient of a 2013 MacArthur Foundation Award for Creative and Effective Institutions.

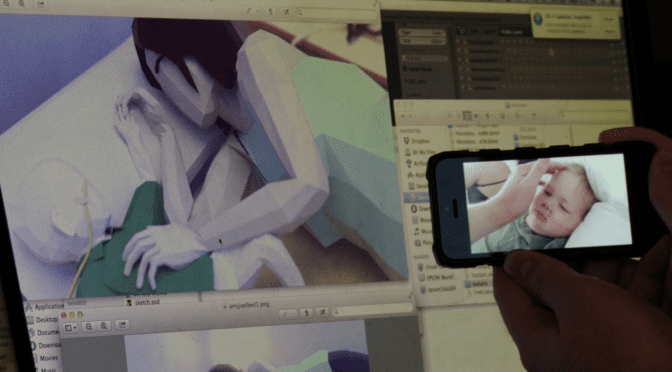

For 18 months, award-winning filmmakers David Osit and Malika Zouhali-Worrall followed Ryan as he created a game called “That Dragon, Cancer,” recruiting his wife and sons into the process of documenting their daily life in Loveland, Colo., for this unusual work of art. Combining footage from both Ryan’s real and animated worlds,Thank You for Playing is a thought-provoking portrait of one family’s determination to respond to an impending tragedy through artistic expression. The film challenges the stereotypical view of video games as superficial or violent, revealing a new movement within the gaming world to create projects that document profound human experiences.

The film also tells a deeply moving love story of a husband and wife helping to keep each other afloat in the midst of a familial crisis by creating something entirely new together. The video game becomes a poetic exploration of a father’s relationship with his son, an interactive painting and a vivid window into the minds of grieving parents.

In Thank You for Playing‘s first scene, we see the game’s portrayal of the day Ryan and Amy are told Joel’s cancer is terminal. Inside a virtual doctor’s office, a terrible storm breaks and rain begins to pour. The room fills with water up to the necks of Ryan and Amy’s digital avatars. Though rendered in animated form, the scene presents the wrenching reality that envelops the Green family—and countless others who have faced similar devastating news.

From the start, Ryan and Amy wanted to redirect the focus on Joel’s illness in a more positive way for their young family, which includes the boy’s two adoring older brothers. Amy, whose inner strength and calm demeanor are constant family anchors, would “much rather live like he’s living than live like he’s dying.” Ryan, whose emotions are never far from the surface, envisions a video game that would allow him to “create a space for me to talk about my son” and allow players to experience the same joy he feels as a father, even in the midst of anguish. The drama is more subtle than that provided by typical video game fare, yet gains unmistakable power as players participate in the family’s daily routine, from feeding ducks to pushing Joel on a swing to reaching out to touch his face as he rests in his hospital room. “You are being a friend with us on this journey,” Amy observes.

Developing the game also gives Ryan a degree of respite. “When you’re creating art there’s a level of abstraction,” he explains. “There’s a certain escape.”

But, he adds, “You can’t escape forever.”

For Ryan and Amy, who are practicing Christians, “That Dragon, Cancer” also becomes a way to explore their faith—a kind of digital prayer created to share their child with the world while they still can.

But as Joel’s cancer advances, it becomes increasingly challenging for Ryan to develop the game. How much should he share? How realistic should the visual portrayal of Joel be? At what point does telling the family’s story become too invasive? From having his sons reenact difficult conversations to recording Joel’s giggle to painstakingly photographing every detail of the hospital, Ryan’s life becomes consumed by the process of creating a digital world that mirrors his family’s reality. He wrestles with the question of whether to record Joel crying. “Do you point a camera at someone on their deathbed? I just don’t know.”

A gaming console company invests in “That Dragon, Cancer,” turning Ryan’s hobby into his family’s sole source of income. Ryan and his small team premiere an early demo at PAX Prime, the biggest gaming conference in the United States, where player after player is moved to tears. Critics cite the game as one of the best at the conference. But in the midst of the game’s success, Joel’s health continues to deteriorate. “I could lose Joel in the next month or two,” says Ryan, his body wracked with sobs. “I just wish I could hold him right now.”

When the doctors diagnose new tumor growth in Joel, Ryan and Amy move the family to San Francisco to enroll him in a last-resort clinical trial. They document this period to include in the video game, “because you wouldn’t want to not capture it, and know you couldn’t go back,” says Amy. At night, while the family is asleep, Ryan continues working on the game, more determined than ever to encode these last moments with his son. “The most compassionate and fulfilling moments of your life can be in the middle of the deepest loss you can experience. I think that can be beautiful. I hope it’s beautiful.”

For filmmakers David Osit and Malika Zouhali-Worrall, Thank You for Playing is an opportunity to challenge people to reexamine their own assumptions about bereavement, technology and video games. “We wanted to transcend the simple narrative of a family dealing with cancer, and instead examine the ways we handle grief, and the beauty and hope that can be found in art,” they say. “We saw how many people were profoundly moved by Ryan’s game, and how playing it often facilitated more, rather than less, social interaction. The fact that a video game was capable of awakening this sort of empathy astounded us, and we soon realized that Ryan isn’t only a developer, he’s also an artist—and programming is his paintbrush.”