The Other Nominees: The Awful Truth; Captains Courageous; Dead End; The Good Earth; In Old Chicago; Lost Horizon; One Hundred Men and a Girl; Stage Door; A Star is Born

The early days of film were a strange time. Pacing, plotting, and tone were whatever the present scene demanded, and it wasn’t out of the ordinary for a film to ricochet not only between tones but seemingly between genres. 1932’s Best Picture winner, Grand Hotel, is a prime exemplar of this, and The Life of Emile Zola, although a better film in its totality, is guilty of it as well. There are three or four movies going on at once here, some better than others, and as a result the film is at times at war with itself.

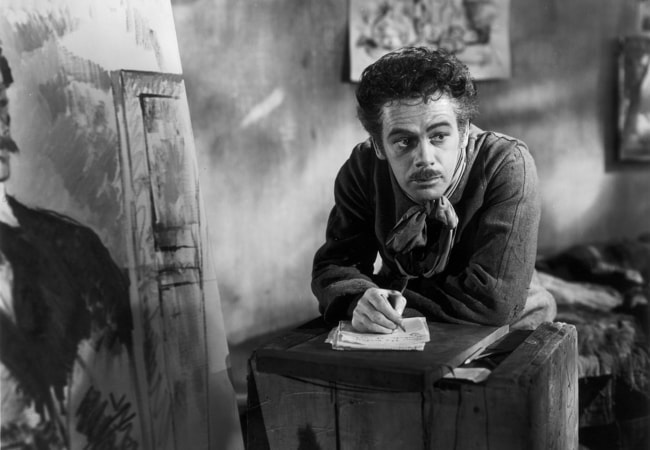

The main problem with The Life of Emile Zola is that it doesn’t want to stay true to its title. To wit: Zola’s life is largely done away with in the first thirty minutes of the film. This isn’t a biography as much as it is a series of vignettes. We meet Zola as a starving (and freezing) artist, living in squalor with Paul Cezanne, the father of modern French painting. Zola doesn’t starve long, though; in this same scene (remember, the very first), his mother and fiancee arrive to tell Zola that they’ve secured him a job with a famous book publisher. No sooner is this connection established than it is destroyed, as the publisher fires Zola for bringing unwanted scrutiny from the police, who show up to warn Zola against publishing any more books like his scandalous Claude’s Confession.

Lest you think that’s anything close to a setback, think again, because Zola makes a name (if not a fortune) for himself by amplifying the unheard voices in France. He befriends a prostitute whose life he adapts into his bestseller Nana, establishing his reputation as not only a muckraker but a scandal-maker as well. I’m being glib, but credit should be given where it’d due: Paul Muni is inspired casting as Zola. He’s more of a presence than an actor, which is a feature and not a bug. Watching someone write is incredibly boring, and the film knows this, so it’s to the film’s benefit that Muni is as watchable as he is, even if his take on Zola rarely moves beyond “insouciant rascal.”

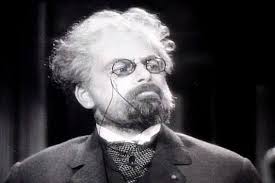

Muni’s performance is almost wasted, though, because the life of Emile Zola is the least interesting thing about The Life of Emile Zola. The meat of the film involves the Dreyfus Affair, in which French military officer Albert Dreyfus was tried and convicted of treason, despite two things: he was innocent, and the military higher-ups knew it. This is where Emile Zola shines brightest; its critical stance toward the Army would be echoed (louder, and better) by later films like The Steel Helmet and Stanley Kubrick’s masterful Paths of Glory. Granted, it’s low-hanging fruit for an American film to cast a critical eye towards a French scandal, but abuses of power by men in uniform is an uncomfortably common problem. In that way, this film can be seen to presage A Few Good Men as well.

Dreyfus’s plot is more compelling than Zola’s, and it doesn’t hurt that the performance – by Joseph Schildkraut, who won a Best Supporting Oscar for his work – eclipses Muni’s in subtlety and nuance. It’s tempting to imagine this film without Zola, which sounds like harsher criticism than it is. If I were to remake this, I’d likely call it The Dreyfus Affair, center the film around Dreyfus, and have Zola emerge near the end, a towering, mythic figure like Anthony Hopkins in Amistad. But it’s pretty egotistical to entertain hypotheticals like this, so let’s move on.

The Life of Emile Zola has its crowd-pleasing moments, to be sure. Some are surely fabricated – a card prefacing the movie basically confirms this – but enough is rooted in historical fact that we don’t feel lied to. Some parts are genuinely rousing, such as Muni’s best moment, a fiery speech given in a newspaper office in which he reads a letter to the president of France, damning the Army for the cowardice and complicity. He knows it will land him in court for libel; he also knows that it’s the only way to reopen the Dreyfus Affair in the public eye.

The movie bills itself as a courtroom drama, which isn’t exactly true, as Zola’s libel case takes up about thirty minutes of the film. Muni is largely silent here, as his lawyer does most of the talking, and one wishes they would have jazzed up these scenes for the audience’s sake. It’s admirable, though: not just Zola’s actions, but the film’s approach to them. Even when Dreyfus isn’t on screen, the movie never forgets him. We even see glimpses of his hellish imprisonment on Devil’s Island, a surprising inclusion for a film nominally about another man entirely.

At times, The Life of Emile Zola feels incredibly dated; you can hear it in Max Steiner’s bombastic score, or see it in the histrionics of Gloria Holden’s performance as Zola’s wife, Alexandrine. But the emotionality of the film has aged nicely. It’s trite to talk about the triumph of the human spirit, but it can be damned moving to see it personified. The Life of Emile Zola is far from perfect, and at times shows its age. But that doesn’t stop the central story from being enthralling.

Previously: The Great Ziegfeld

Next Up: You Can’t Take It With You