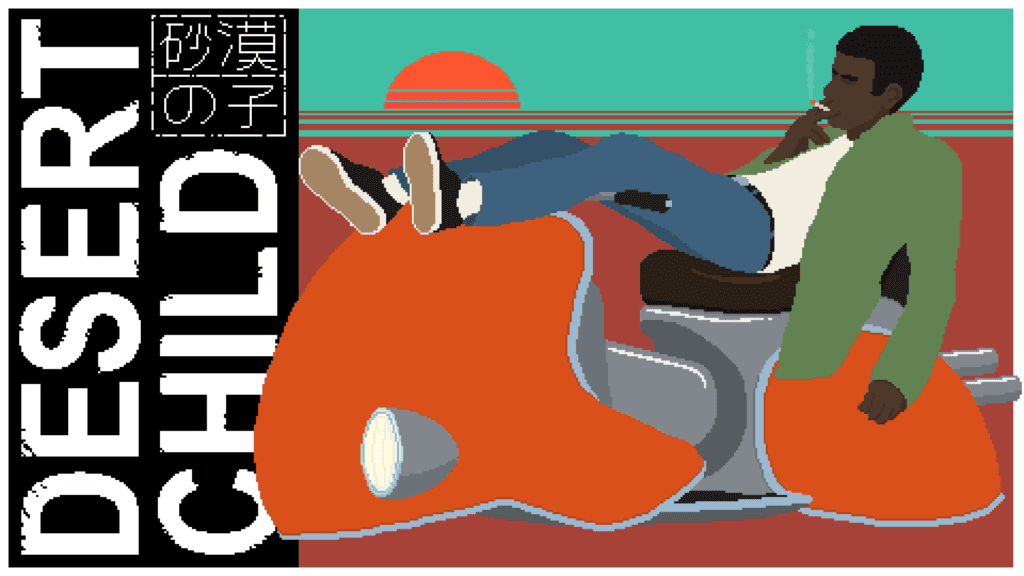

Desert Child from Akupara Games is a visual marvel that is hard not to fall in love with on appearances alone. Visually inspired by early ’90s Sierra DOS games and the future world of Cowboy Bebop, Desert Child will easily draw a player in with its slick look.

What’s hard to understand is that Desert Child is more or less a racing game that’s stuffed inside an art project. I don’t mean that as a negative, only that the game has no defined core, happy to let you live within the weird and awesome world it presents.

You play as a dude with a wicked cool hoverbike, just trying to make it on the red planet of Mars. Your skills make you one heck of a racer and with that comes opportunity. Mostly the opportunity to make a lot of money and earn some street cred along the way.

Under the surface of the amazing visual style and presentation, Desert Child is a pretty basic racing game with some SHMUP aspects. You take races and do your best to compete against other hoverbike racers in an attempt to get to the end of a scrolling stage first.

During this you can boost for speed and shoot items that attack you or drop cash while dealing with your opponent. And that’s it. Gameplay is as basic as it gets, simply wrapped around a gorgeous presentation. As you compete in races you earn cash, cash that you need to save to enter the Mars Grand Prix, where you earn even more money.

That’s the gist of the story. You want to win the tournament and get money to buy all the sweet upgrades for your hoverbike. There really isn’t any motivation for this other than you being a good racer. There is no narrative to buffer the amazing look presented which is a darn shame.

Desert Child is interesting because it plays as much like a normal simulation game outside the racing bits. Your bike will take damage and you’ll have to invest money in getting it fixed, you’ll get hungry and have to eat, and you’ll need to upgrade your ride to stay competitive.

This is where the bulk of the game lies. Working to manage your money so that you can earn the $10,000 you need to enter the Grand Prix where the game ultimately ends. You simply live your digital life and get lost in the world presented, win the big race and that’s that.

But you won’t just be racing as Desert Child offers a number of opportunities to earn money with your skills. You can deliver pizza, hunt bounties, and take part in some shady dealings including throwing races and robbing digital banks which risk alerting the space police.

These things all sound fantastic, and most are the first few times you play them, but they are all built on top of the same basic racing gameplay. In stead of racing an opponent you just work to shoot them to death in bounty mode, you throw pizzas to customers instead of shooting, and you blast Windows logos and vaporwave busts in the heists.

These segments are punctuated by some incredible music, but after a few times through each you quickly see the limitations of the gameplay engine used by Desert Child. It simply does not have enough depth other than to be a fun diversion rather than a full-fledged gaming experience. It often feels more art than actual game.

You run a race or do a job and then fix your bike and eat some food. You buy an upgrade and deposit you money in the bank to earn interest. You take side jobs like being a race tutor (simply racing against someone) or herd kangaroos using your bike.

Where Desert Child tries to keep you going is with the world that it presents the player. You get an almost RPG-like feel as you walk around and explore Mars much like you would in an old Sierra game. Along the way you’ll get all sorts of inside jokes, references secrets that are a really nice touch.

The coolest part of the game, outside the visuals, is the music choices Desert Child presents. Mars has one heck of a record shop where you can buy records using in-game cash that change the games soundtrack. The music is so good that I had to pause the game just to track down the artists. This is the sort of game that I’d kill to have a soundtrack on vinyl for.

The game offers a number of secrets and while the gameplay is barebones, there is this pull the game seemed to have had over me. It’s the kind of game that you’ll think about long after you’ve stopped playing because of how unique it is. The game even includes a “Chill” option where you simply hangout out on your bike and enjoy the overall vibe presented.

Visually, I adore Desert Child. Growing up with titles that looked like this on PC this one really struck a chord and I can easily say without question that it has the best soundtrack of the year. Unfortunately, the gameplay just isn’t developed enough or deep enough to match the caliber of everything else on display. And it’s also a pretty short experience.

I got to play the game on release through the Utomik gaming service that works like a Netflix but for games. In this regard it’s an incredible value since I have access to a library of games, so much like watching an okay film of Netflix you don’t feel cheated with so many other options.

If you go through Steam you’ll only pay a flat $11.99, and for that price I can still easily recommend Desert Child, especially for those looking for unique games with a wicked sense of style. It might not be a deep or long experience, but it’s one you’ll remember, and that’s more than can be said of most games released this year.

“Desert Child is a visual and auditory treat that unfortunately feels more like a slick tech demo than a complete game.”

Final Score:

2.5/5