Biopics, particularly of musicians, have become so cliché at this point that it can sometimes be a wonder any filmmakers even bother anymore. As a genre they can often play as straightforwardly unironic and blush inducing as any romantic picture. With Jimi: All Is By My Side writer and first-time director John Ridley has crafted a movie that doesn’t tick off any of the usual boxes nor does it feel like award-season bait. Don’t expect tearful reunions between estranged family members and don’t hold your breath for sensational depictions of fame and partying on the road either. Parodying this peculiar depiction of a single year in Jimi Hendrix’s life à la Walk Hard would be a challenge. Appreciating it as anything other than some abstract take on what these biographical movies can be isn’t that much easier. This is one strange and moody brew.

Ridley appears to have self-consciously arranged the film to avoid virtually anything typical or expected. It’s hopefully not divulging too much to note that All is by My Side actually ends with Jimi and his band mates about to head to the States for the Monterey Pop Festival that made them huge stars. It’s exactly where most pictures like this would start–and that feels like the point. We watch as an unknown Jimmy James (played, of course, by André Benjamin) over performs as a background guitar player for other acts, clearly underemployed and underutilized. He crosses paths with Linda Keith, the girlfriend of Keith Richards, who is immediately taken by his talent and personal magnetism. She prods him to sing against his reservations and brings people in the know out to see him jam in clubs (“He’s less than nothing: he’s rubbish!” declares the Rolling Stones manager). Things only change when the bassist from the Animals, Michael Jeffrey (played by Burn Gorman), leaves performing behind and takes up managing him. Unlike the others, he’s impressed right away by Hendrix’s playing and encourages him to leave New York for the greener pastures of London.

It’s in London that Hendrix, in many ways, becomes the legend still revered today. He buys groovier clothes. He puts together a formidable rhythm section. And he meets Kathy Etchingham (Hayley Atwell), who became his girlfriend and muse. It’s in that relationship that Ridley needlessly courts controversy and is somewhat baffling. He includes two scenes that forcefully suggest a dark side to Hendrix’s personality. In the first, Jimi amusedly looks on as Jeffrey gratuitously insults her for squandering precious studio time. After the band has finished recording, he’s legitimately surprised when she’s mad that he didn’t defend her and a full on shoving match ensues. Lest the violent undertones in that scene be too subtle, in another he fumes when she disrespects him by dialing another man. He responds by grabbing the phone from her hand and repeatedly brutally striking her with it until he’s dragged away. The thing is those moments seems jarring for purely for the sake of it. It doesn’t conform to what’s been said about Hendrix and Etchingham for her part firmly maintains that nothing of the sort ever happened between them.

Ridley, fresh off his Oscar win for penning the 12 Years a Slave screenplay, certainly has creative license to go wherever he wants. It’s on the issue of race that he makes some of his sharpest points. In a recreation of an incident that actually happened to Hendrix during his time in London, a pack of cops menacingly surround him. At first they express strong disapproval for his wearing-and thus, disgracing-British military garb. It’s quickly apparent though as they chide him that they’re just as unhappy about the white English girlfriend in his arms and what he represents walking around their Anglo streets. No one uses the ‘N’ word or utters anything else quite that overt, but the strong racial overtones are clear, and certainly so for the young couple. In another scene he meets for tea with the civil rights activist Michael X who chides him from the other side for not being a radical (“If you’re going up on that stage just to go up on that stage, you’re wasting yourself”). He tells him that English racism is less obvious than the American strain, but never to forget that it’s there–like when the press refers to his guitar playing as “violent”, but not Eric Clapton’s. You’re left with the impression of a man very aware of race and discrimination-and how as a black American he was more or less an anomaly in the English blues-rock world-yet with faith only in affecting people through music, not marches or quixotic statements.

His timeless music surely would provide a statement enough for the film and a solid backbeat. Unfortunately Ridley didn’t have the consent of the Hendrix estate, which meant that he lacked access to the man’s catalog. The best he can do in its place is some bluesy noodling and tunes from before Are You Experienced and later a full-throated rendition of Jimi’s “Sgt. Pepper” cover from the Saville Theater show (you’ll hear more Dylan songs). What the movie does point out rather saliently-even without the benefit of listening to Purple Haze” or his greatest song “Manic Depression”-is how rock music was something that he transitioned into from other genres instead of emerging from it (making the case for bringing on Mitch Mitchell on drums, he compares him favorably with the jazz drummer Elvin Jones). “I want people to feel the music the way I see it”, he explains of his grand artistic ambitions. For much of All is by My Side he’s impatiently on the cusp of fame and making the masses feel things from his music, wondering how it could be that his songs aren’t cracking the top 100 and why the reviews aren’t kinder.

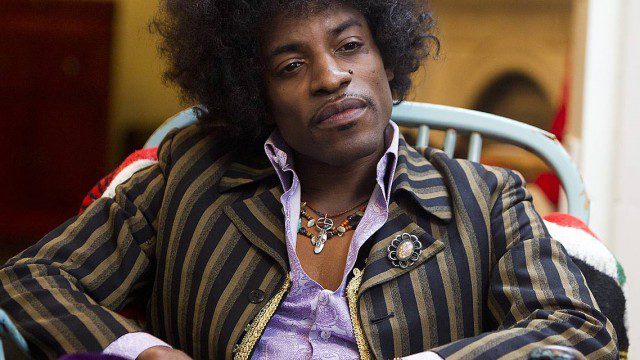

As Hendrix, Andre Benjamin is as captivating as the movie permits him to be. This isn’t one of those precise impersonations like Chadwick Boseman’s brilliant turn as James Brown on Get On Up earlier this year. Instead it’s something subtler yet equally ambitious: a meditation on the idea of Hendrix as much as it is the man himself. Casting someone famous and recognizable as he is in his own right for making great music could have been a distraction but Benjamin finds the right unshow tone and sustains it. The women, Imogen Poots (who as Linda Keith looks like a young Helen Mirren here and is missed when not onscreen) and Hayley Atwell, are excellent as well.

You get the sense that John Ridley wants his filmmaking more than anyone or anything else to be the star. He shows cold competence in his first time behind the director’s chair, but not enough beyond that. The approach is consistently too fussy from his stubbornly anti-biopic writing to the weird stylistic touches he infuses the movie with (the oddest-I think-is when he cuts to Hendrix onstage but shuts off the sound of the amplified notes so you just hear his fingers tapping the strings). The first act is surprisingly prosaic and tedious and it never builds up from there to any release. Visually too the movie is washed out and nondescript. There is scant sense of era and few visual clues to it being the mid-1960s beyond a general absence of smart phones and iPods. The lack of Hendrix’s music becomes unbearably drab and though Ridley might not have been able to help that, it still makes the picture feel desiccated and pretentious. All is By My Side is at its best in its loosest, liveliest moments: Hendrix teaching his band a brand new Beatles song on the spot knowing they’re in the audience, outplaying Eric Clapton at a concert, the sexual tension with Linda Keith. Everywhere else it’s too often clock-watching and dreary; an odds and ends of things you haven’t yet seen in a biopic because most other directors have a shockingly square attachment to entertainment value.