What if you were able to use all of your brain instead of just a small fraction of it? That’s the startlingly misinformed question asked in Lucy, a part-stupid, part-insane thriller by writer and director Luc Besson. Ludicrous is one thing. Dumb or poorly executed is something else altogether. Even movies that are on the borderline can be exceedingly well made and entertaining (Speed, anyone?) and I was prepared to laugh at its ridiculousness while digging the action.

Lucy, however, is a movie premised on a fallacy and ideas stemming from it so jaw dropping, with pretensions so abundant, that it only serves to make the dumbness and crudeness of it all the more glaring. There might have been a silly, yet solid grade-B thriller buried under all the muck, but Besson’s approach is nearly as tedious as his science is dubious.

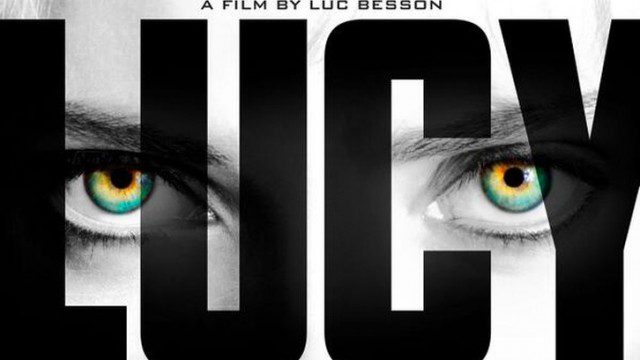

Scarlett Johansson plays Lucy (she only gets a first name), a 25-year old studying in Taiwan. The movie starts rather shrilly and suddenly as her new boyfriend (a grinning sleaze with a European accent and an outfit like Bono) tries to convince her to make a handoff to Mr. Jang, a crime boss. When he can’t talk her into doing the job he simply cuffs her and gives her no choice but to go take his place. When she does, he’s quickly killed and she is taken captive by the gangster’s men.

The substance she’s transported is-after much tension and forbearing-revealed to be a synthetic version of CPH4, a dangerous trial drug that delivers a swift exhilarating high when snorted and can dramatically increase the user’s cerebral capacity. The goons cut her open (along with some other guys) and force her to be a drug mule. That plan is halted when a brutal kick from one of the men causes the bag to leak and she begins amassing incredible new powers—(the first of which is to break free and shoot them all dead).

Things get more chaotic and head scratching from there, but Johansson’s star-power unsurprisingly proves to be one of the more consistent and favorable qualities. It’s the type of action-flick acting that doesn’t require the most eloquence or nuance and she’s more than adequate in a forceful, ruthless role where she gains all the power humanity is capable of at the same time she falls apart.

If there’s a new slowly developing trend toward female super-heroes and action stars, it’s a welcome one (even if her character is hardly virtuous or noble) and she’s fit to lead the pack. At the same time, her role here feels like a faint echo of the one she had earlier this year in the vastly darker and more intriguing Under the Skin, Jonathan Glazer’s uncompromising and unnerving art-house thriller.

The relatively more straightforward Lucy becomes a countdown to her tracing the location of the other mules so that she can recover the drugs, while the law and the crime boss pursue her. The movie assumes that human beings can only use 10% of their brain and gives an update every time her percentage increases. At 20% she’s just insanely tough and whip-smart. Apparently by 50% she can collapse an entire hallway of heavily armed cops telepathically. By 90% not even time can stop her as she can instantaneously travel through time and space at will, obviously.

Somewhere along the way it brings Lucy’s attention to a professor of neuroscience in Paris focused on exploring the very questions her freak urgent case poses. Played by Morgan Freeman, this impeccably fine and reliable actor has rarely seemed more grandfatherly and warm than he does here. He’s a performer who naturally exudes intelligence and wisdom whatever the setting and that’s what lets him come out largely unscathed. Freeman even makes the college hall lecture he gives outlining the movie’s silly ideas about brain capacity throughout the animal kingdom seem almost credible for a minute or two, solely on the authority of his voice.

It’s Besson’s voice that speaks with notably less command. How someone, even a big director like him, wrote and was then able to make a movie based on a completely misinformed premise like this in the age of Google searches is a mystery. Human beings don’t just use a fraction of their brains–which most people really should know already.

All the analysis I’ve seen from experts in the field suggests it’s wrong no matter how you slice it (most salient point comes from Jane Hu writing at Slate: cells tend to atrophy unused, meaning that most of our brain would wither away). Besson comes at it with a bold certitude, no doubt. I kept thinking of the classic Calvin and Hobbes strip where he writes a report for school all about how bats are bugs, without a shred of second-guessing about that laughably wrong and easily refutable assertion.

The silliness of the picture might have worked if he exercised more control and discipline over it. Lucy surely would have played better straight, untarnished from all his weird, winking touches and cues. Even before the movie turns utterly preposterous he can’t help but interrupt scenes with portentous images of animals out for the hunt (those are spliced in with the drug handoff gone wrong scene at the beginning) or a rat sniffing cheese on a trap (her scuzzy boyfriend trying to convince her beforehand) and ponderous, yet indifferent questions about what we’ve done with a billion years of life on earth.

A montage of early pre-Homo sapiens man feels nearly satirical and by the time the professor’s thoughts on immortality vs. reproduction gets trampled on by shots of rhinos, frogs, and others having sex (along with humans in the backseat of a car), he’s really pushing it. There’s a jarring lack of rhythm or sustain. Besson has to busy too many scenes up–even Lucy guzzling a glass of water has multiple jump cuts. The badness of the movie, despite a handful of entertaining moments (her return to exact a deliciously vicious partial-revenge on Mr. Jang is admittedly great), gets harder to turn away from as it builds to its loud, effects-heavy climax. Lucy is a triumph of bigness, all right, but it’s of budget, not brain capacity.