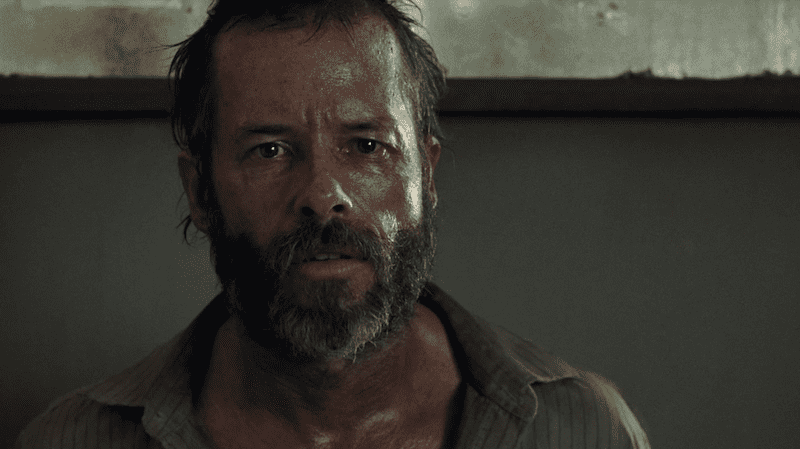

Guy Pearce has always been an actor of more presence than depth. The performances he’s given to date have tended to be mostly passable in terms of sheer technique. It’s hard to think of any glaring or embarrassing missteps he’s made. And yet there’s an air of superficiality to nearly all of his performances that prevents them from lingering very long when they’re over. That’s what makes his terse, scantly worded part in The Rover at first ideal for him and then surprising. While he’s initially depicted as a ruthless man with little more than a name and a singular focus to get back what’s taken from him, his acting gradually develops a genuinely grieving and mournful quality. By the end he’s quietly devastating, achieving more than an intriguing presence or mystique, but a real resonance.

The world he inhabits is one that’s somewhere between our own at present and Mad Max. It’s Australia ten years after society has been uprooted and dismantled by a global collapse. God and men of authority exist, but neither will do anything to spare you from harm. The guy who runs the gas station or the local shop owner will only provide assistance, no matter how important, if you buy something—and American dollars only, mate. And good folk keep their dogs locked up in cages, not to be cruel, but to protect them from being snatched and eaten.

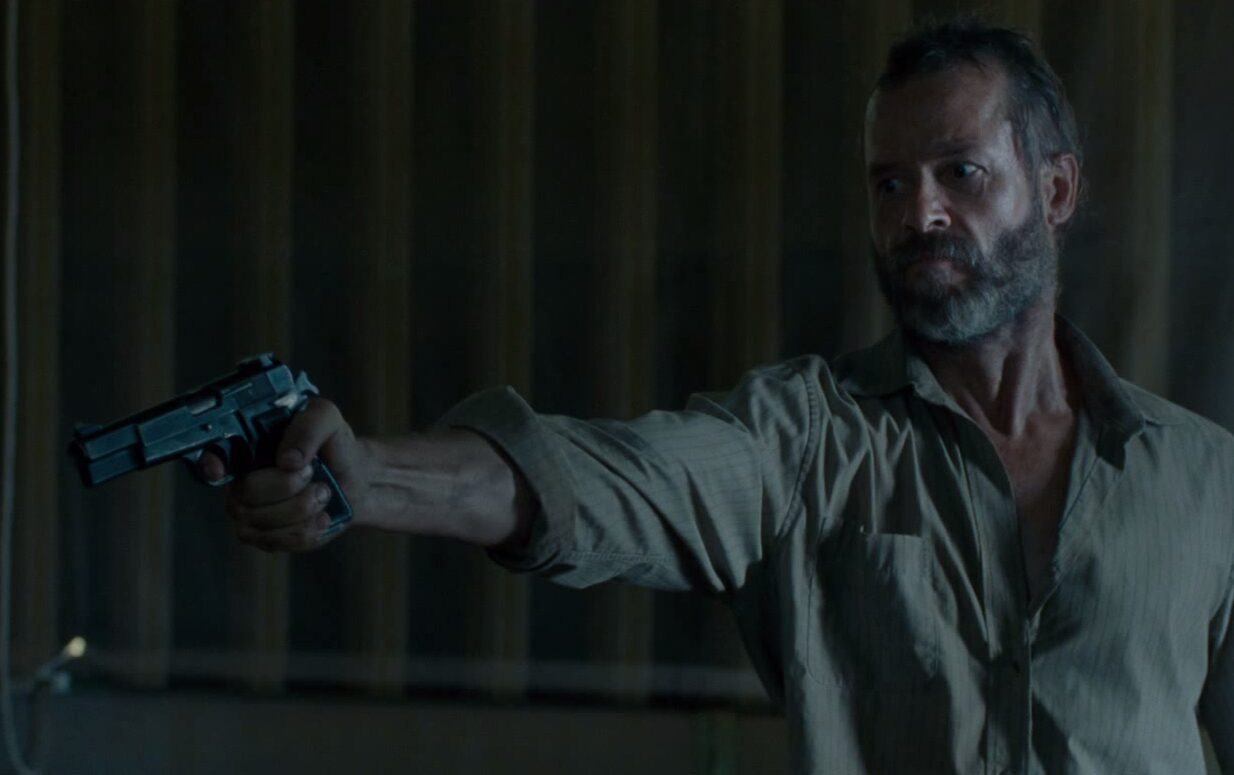

Pearce plays Eric, a man who we see drinking alone when The Rover starts. At the same time three men flee a crime scene, having left behind the leader of the small pack’s younger, helpless brother, bloody and dying by the side of the road. When they get into a wreck along the way they just do like outlaws do and randomly steal the car that happens to be Eric’s. Enraged, he immediately hijacks a vehicle and pursues them demanding they return what’s his. It is to no avail: in the middle of their confrontation one of them knocks him unconscious and they drive away.

He awakens determined to find them and exact revenge. Shedding blood for retribution or sheer necessity appears to come naturally to him. In one of the few facts he reveals about himself, we learn that he was a farmer before the world went sour. He disposes of human life with all the dutiful precision and hard heartedness that someone would relieve sick animals of their misery or handle even more mundane tasks. When a gun dealer refuses to budge on the asking price, he simply splatters his brains all over the trailer wall. And yet, it’s never quite that easy. “You should never stop thinking about a life you’ve taken. That’s the price you pay for taking it”, he tells Rey, the young man who was abandoned by the side of the road. He rescues him by finding medical help, but then forces him to lead the way to his older brother. The Rover, already a downbeat picture, becomes even more so when Rey mistakenly guns down an innocent girl. The weight of guilt for terrible mistakes you can never undo is heavy indeed.

The dynamic between the two men, a relationship fundamentally between captor and prisoner, develops into without descending into clichés. Eric first compels him, and then convinces him to turn on his older brother. There’s more however to this simple man than initially meets the eye. The same goes for Robert Pattinson and his squinting, stuttering performance. It seemed like an odd casting decision, and probably it was. He’s surprisingly good though performing opposite Pearce, playing someone who’s more out of his element emotionally than physically in this bloody, uncivilized terrain. Pattinson, voicing him with a distinctive backwater drawl, makes him a largely sympathetic loser.

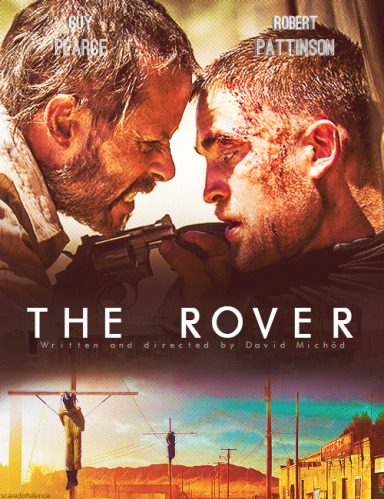

This is the second feature film from Australian writer and director David Michôd following 2010’s Animal Kingdom. I thought that movie-praised by many-dawdled too much and tripped along its small colloquial talk despite its exceptionally fine cast. Here he wisely dispenses with lengthy passages of dialogue in favor of a bleak, blunt nihilistic visual poetry. He has an impeccable eye for the horrors of a receding civilization (the cinematography by Natasha Braier is stunning). The desert locales are vast and desolate, the roads too are mostly empty, and the telephone poles peppered with corpses hung out for the crucifixion. Occasionally his direction even has a hint of the surreal, like the deadpan sight of a car spinning around into a chaotic wreck right outside the bar window as Pearce downs another drink.

The Rover is a modern outback-western thriller and an existentialist dystopia-noir. The movie is also borderline monotonous, devoid of any humor, and absent nearly any women (apart from the doctor and a mysterious older lady who won’t cooperate with-or cower from-Eric). It nevertheless builds to an uncommonly tense and despairing conclusion. This is a thoroughly depressing film in ways that may or may not work for you. I found it to be brilliant and vastly better than it had any right to be, though I couldn’t always explain why. Michôd’s vision is brutally uncompromising, that much is perfectly clear. The now mixed reaction to The Rover may very well be reevaluated in due time, to its favor. The evidence is all right there in its deliberate storytelling and Pearce’s tough, haunting portrayal of what a man with absolutely nothing left becomes.