“I’m hideous, doctor! I’m crazy! I’m a monster!”

Watching early David Cronenberg films is like listening to a band’s demo tape. You can sense the themes and iconography that he would later hone to perfection, but perhaps at this moment muddled by some feedback or other signals. Cronenberg’s 1977 film Rabid is many things: disorienting, shocking, occasionally frustrating, at least once breathtakingly erotic, subversive, feminist, and about as subtle as a sledgehammer. It’s proudly, almost defiantly, a B-movie, but if we’re sticking with that demo tape analogy, this is one of the songs with the most promise.

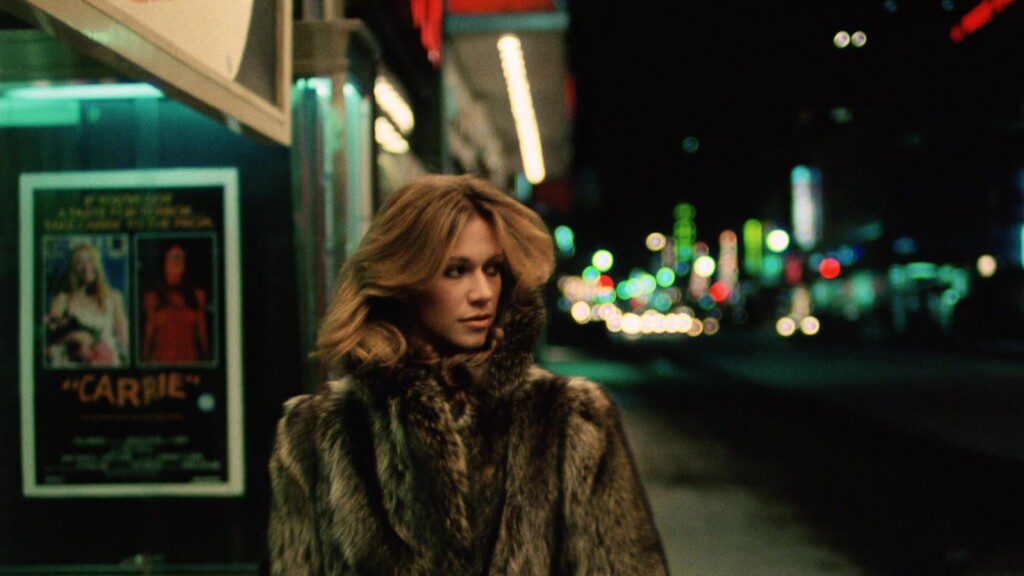

We meet Rose as she waits for her boyfriend, Hart, outside of a convenience store. Rose is played by Marilyn Chambers, then best-known as the face of Ivory Snow detergent and for starring in glossy pornographic productions, the most famous of which was Behind the Green Door. It was a pre-Ghostbusters Ivan Reitman who suggested her casting (Cronenberg wanted Sissy Spacek), and it’s easy to see why. The camera adores Chambers. I’m not going to spend too much time ogling her, but she’s an uncommonly beautiful woman; even more than that, she has presence. The eye is naturally drawn to her, and even if her performance is so-so, Rabid, strangely, doesn’t suffer for that. The same can’t be said of Frank Moore, who plays Hart and is about as exciting as dishwater.

Rose and Hart get into a horrific motorcycle crash, which luckily happens a few miles away from a plastic surgery center. The head physician, Dr. Keloid, proclaims Hart more or less okay, save for a few broken bones and a concussion. Rose, however, needs surgery right away. Keloid uses experimental skin grafts on Rose, and everything turns out just fine. Wait, scratch that: the opposite. Rose develops a new orifice under her arm and can now only subsist on human blood. That might sound like an inconvenient spot, but men in this movie are constantly trying to get their hands on Rose; in one telling scene, she screams herself awake and within moments is being hugged by another patient. While topless.

Out of Rose’s orifice (I’m sorry, I don’t now how else to put it) comes something akin to a stinger or an ovipositor. Like I said, subtle as a sledgehammer. The imagery in Rabid is phallic, vaginal, even clitoral, sometimes all in the same scene. In hindsight, Reitman’s suggestion of Chambers was right on the money. For a movie about the entitlement men feel towards women’s bodies, who better to embody that than a professional adult entertainer?

Lloyd – the patient who comforted Rose when she awoke – leaves the clinic, not very concerned with the wound on his side that won’t clot. “It’ll slow to a trickle,” he says, which actually makes a kind of sense, coming as it does from someone who routinely gets voluntary surgery. Of course it doesn’t, and in a cab Lloyd turns, I’m just gonna say it, rabid. The car crashes, falls off a bridge, and is then hit by a semi, and it’s one of those practical scenes that make it a pleasure to watch old horror movies. It’s here that Rabid switches from body horror to something more like a zombie movie, and also where it starts to lose its way.

From this point on, Rabid focuses less on Rose and her transformation and more on what the rapidly spreading infection is doing to the country. We see various people interacting with Rose and winding up infected, but Rose herself is let down by Cronenberg’s screenplay and never granted much interiority. To be fair, the vignettes, as I’ll call them, where Rose meets and infects people are well-done. There’s care put into the staging of them, and enough detail is given that the vignettes carry some verisimilitude. The timeline gets frustratingly muddled, though. Rose seems to leave and return to the clinic seemingly at random, but what’s most frustrating is Hart’s out-of-nowhere friendship with Murray, Dr. Keloid’s business partner. They don’t even seem like new friends; they have the easy camaraderie and comfortable silence of people who have known each other a long time. If the film explains this, I missed it.

Rabid is at its most ruthlessly efficient when showing the rapid deterioration of society, but it’s at its most humane – and effective – in its quieter moments. The saddest part of Rose’s affliction is that it doesn’t turn her into a mindless zombie, or send her into a fugue state. She’s wide-eyed and lucid when she’s attacking and feeding on people, but it’s as if she’s on auto-pilot. The wound is in the driver’s seat, which is why, even after killing a handful of people, she denies being a killer. This leads to Rabid’s best scene, in which she attacks a desk clerk and locks herself in a room with him, certain that he’ll stay dead and she can prove she’s not the carrier of this horrible virus. This is also Moore’s finest moment, as he pleads with her over the phone to leave; when she refuses, he breaks down into an almost primal wail, smashing the phone because there’s nothing else he can do.

Rabid is certainly uneven, but I’d recommend it nonetheless. It’s fascinating to watch Cronenberg operating with such a limited budget, but not letting that deter him from exploring the same themes he’s spent his storied career delving into. The budget on this thing was one million dollars. Most directors couldn’t do with ten million what Cronenberg did here.