“Would you like to meet a ghost?”

The best kind of horror, to me, is the kind that traffics in dread as opposed to shock. American horror, outside of the indie and arthouse scenes, has been dumbed down to a cacophonous series of jump scares to complement its seemingly endless parade of gore. I’m not opposed to either of those things – The Conjuring has one of the best jump scares of all time – but it’s more surprising than terrifying. The same cannot be said of Japanese horror. (I’m no snob; my two favorite horror films, The Thing and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, were both directed by Americans.) Japanese culture is steeped in folklore and mythology; the line between the real and the unreal is gossamer-thing. That’s what makes Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s masterwork Kairo so elegant and effective. Like the best works of Japanese horror – Cure, Noroi: The Curse – Kairo makes us feel that there is something wrong with the world.

Taguchi is missing from work, which is unlike him. Michi volunteers to go to his apartment and check on him. It’s on her journey to Taguchi that we see Kairo’s muted, intentionally dab color palette on display, which Kurosawa will later subvert to chilling effect. Taguchi seems like himself, more or less, but as Michi makes her way through his apartment, she sees his visibly decaying corpse – hanged with an electrical wire – slumped over in the corner of a room. Taguchi’s corpse is not newly dead, begging the question: who was Michi talking to? What sets Kairo apart from its contemporaries is that here the ghosts just look like people, which is what they are.

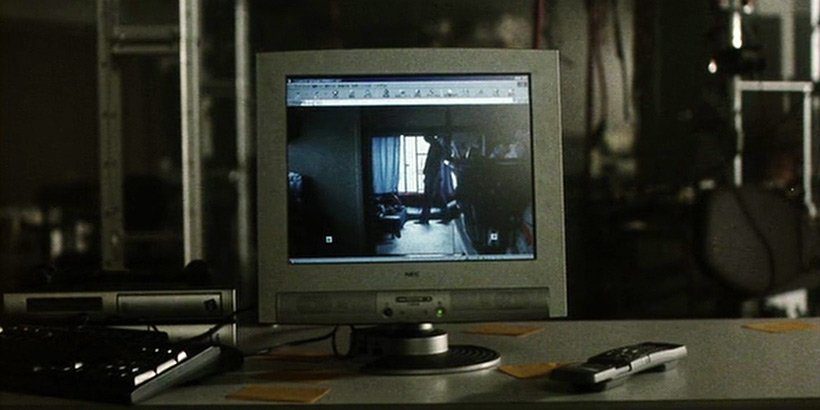

Elsewhere, a university student named Ryosuke is experimenting with the Internet; before long he’s subjected to a series of disturbing images that move him to turn off the computer. It turns itself back on in the middle of the night. He talks to a computer science major named Harue, who advises him to take a screenshot if it happens again. The computer won’t listen to Ryosuke’s commands, but it does show him footage of a man with a bag over his head, in front of a wall on which is written “Help me” over and over. These two stories – Michi’s and Ryosuke’s – will dovetail in harrowing fashion near Kairo’s jaw-dropping climax.

Kurosawa builds an atmosphere of omnipresent dread that permeates every second of Kairo. Beyond dread, there’s an indefinable sense of wrongness to what we’re watching. Still images become recursive, replicating in almost memetic fashion to hypnotic, white-knuckle effect. The scariest scene in the film – and one of the scariest ever, in my opinion – features a ghostly woman gradually walking towards Michi’s coworker Toshio. The slow approach is harrowing enough, but she begins what can only be described as a dance or a pantomime. You’ve never seen its like.

Beyond dread, what Kairo conveys most poignantly is loneliness. The city of Tokyo is practically deserted, and becomes ever more so as the film progresses. The empty streets are eerie, reminiscent of the empty London in 28 Days Later or the abandoned Times Square in Vanilla Sky. A character posits to Toshio that what they’re experiencing is a massive influx of ghosts. When there’s no more room in hell, they say, the dead will walk the earth. That’s what’s so masterful about Kairo’s presentation of its ghosts, and the underlying mythology thereof. We see some people die on screen, via suicide, and others simply become ghosts seemingly naturally, due to sadness, loneliness, the desperate, human need for any kind of connection or community.

Throughout the film are scattered Forbidden Rooms, some of Kairo’s most effective imagery. They’re ordinary doors or windows bordered in red tape, the brightness of which stands in stark, naked contrast to the film’s otherwise muted color palette. It’s in these Rooms that the dead can cross over, and when Ryosuke finds himself trapped in one, he comes face to face with a ghost who tells him what death is. “Death,” the ghost says, “was eternal loneliness.”

When Ryosuke leaves the Forbidden Room, Tokyo is crumbling. A plane crashes and the film barely makes note of it. As the only country to have nuclear weapons used against it, there’s an idea in Japanese culture that cities are impermanent, temporary. But the dead live forever. At what point do we stop mourning our dead?

At what point do we become them, whether or not we’re still alive?