“Do you read Sutter Cane?”

John Carpenter was so ubiquitious in the 1980s that it’s easy to think that he fell off in the ’90s. There was the poorly-received Memoirs of An Invisible Man and the inessential remake of Village of the Damned. But to write the man off entirely would be a mistake. In the Mouth of Madness proved that not only could the lion still roar, but it remains one of Carpenter’s scariest, most ambitious films, well, ever. It’s horror on an existential level he hadn’t previously explored, and there is true despair in the idea that we live our lives at the whim of a god who is worse than indifferent: he’s hateful.

John Carpenter and H.P. Lovecraft don’t sound like a great mix, at first glance. Carpenter works best on a small scale with a small budget; his characters are wiseasses who typically don’t take anything, including themselves, too seriously. Lovecraft, on the other hand, is nothing but large-scale storytelling, as is the way with cosmic horror. The end of the world is never too far away. Which is why Carpenter and Lovecraft were actually a perfect match, as Carpenter found inspiration to cap off his Apocalypse Trilogy (which started with The Thing and continued with Prince of Darkness). While In the Mouth of Madness isn’t based on any particular Lovecraft story, the film wears its influence on its sleeve, and wouldn’t exist without Lovecraft (the film’s title is a play on Lovecraft’s seminal novel, At the Mountains of Madness).

One of the best parts of this incredibly rad movie is Sam Neill in the lead role. Neill is ridiculously handsome, with a mellifluent purr of a Kiwi accent. That said, he’s never been one to shy away from genre fare, like Event Horizon or Jurassic Park, and like in those films, he approaches his role of insurance investigator John Trent here with the utmost seriousness. The role is not without humor, however; he plays Trent with the insouciant charm of a Humphrey Bogart or a Clark Gable. This might be the only horror film I’ve ever seen that reminded me at times of It Happened One Night.

Like all the best Lovecraft stories, In the Mouth of Madness starts in the middle of things. Little time is wasted on setup; we get one scene showing Trent in action as an investigator, and a few minutes later he’s being attacked by a maniac with an axe who demands to know: “Do you read Sutter Cane?” In due course, it’s revealed that bestselling author Sutter Cane is missing, and the maniac was none other than his agent (quips Trent: “For a guy who outsells Stephen King, you’d think he could afford better representation”). Trent is hired by Arcane, Cane’s publisher, to track him down. Cane’s editor, Linda, is along for the ride.

Right away Trent is suspicious about all of this, ready to write it off as a publicity stunt. (This, too, is in line with a lot of Lovecraft narratives. “The Call of the Cthulhu” is as much as a mystery as it is a horror story.) He discovers that the covers to Cane’s books lead to a New England town called Hobb’s End, thought only to exist in Cane’s fiction (Cane’s book The Hobb’s End Horror is a reference to Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror”). Things get eerie right away. The road beneath the car turns to sky; a young boy on a bike passes the car twice, but on the second pass he’s an old man, moaning “He won’t let me leave.” There’s a lot of mythos to unpack in In the Mouth of Madness, and it’s good that it found a home with John Carpenter, a famously economical director. He somehow manages to make an epic in 100 minutes.

It helps that things start going wrong right away when Trent and Linda arrive in Hobb’s End (they stay at the Pickman Hotel, a reference to Lovecraft’s “Pickman’s Model”). They learn that not only has Cane (played by Jurgen Prochnow) taken over the town, he’s created it from scratch. (Near the end of the film, a townsperson laments: “I don’t remember what came first, us or the book.”) The Lovecraftian horror is present throughout – at one point Linda reads from one of Cane’s book; the passage in question is actually taken from Lovecraft’s “The Rats in the Walls” – but In the Mouth of Madness has more on its mind than fan service. At this point in his career Carpenter could have easily gotten the rights to any Lovecraft story – hell, Cthulhu is public domain and even showed up in last year’s Underwater, as well in Nadia Bulkin’s superb collection of stories, She Said Destroy. Carpenter’s film is metatextual in a way that is unheard of for a major studio release (credit is also due to the film’s screenwriter, Michael de Luca, who wrote this movie and four others before becoming a powerhouse producer).

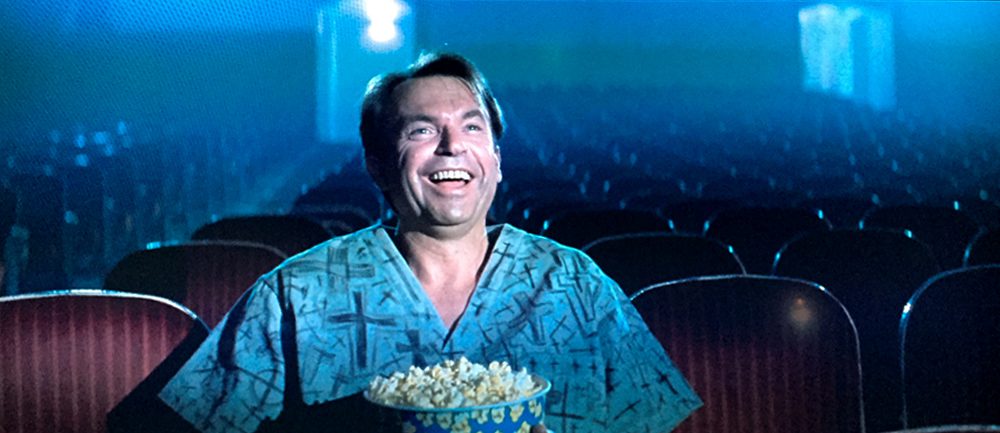

As the film progresses, and Trent further unravels, we’re shown that everything in the world is as Cane wrote it (for something similar, check out Jonathan Carroll’s The Land of Laughs) – or at least, everything in Hobb’s End. Here’s where the film zooms out even further. Maybe they didn’t adapt an established Lovecraft story because Lovecraft exists in this universe; that would explain all the cutesy references in Cane’s work. Cane serves a race of horrible, unhuman things; the more people read his work, the thinner the fabric between their world and ours becomes, until it finally snaps. This comes to a head in the film’s absolutely gonzo climax, in which Trent wanders out of an insane asylum and stumbles into a movie. The title? In the Mouth of Madness. He watches what we just watched; it’s a character in a book watching a movie based on that character in that book. Trent is not simply peering into the mouth of madness; he never left it. The camera focuses on Trent’s disbelieving face before he breaks into peals of hysterical laughter. Cut to black.

In the Mouth of Madness is one of Carpenter’s most ambitious works, as well as one of his best (honestly, it’s probably his last great movie). He’s operating on a scale that we’d never seen from him, and for the second time in his career (after 1983’s Christine) he allows himself to be put in conversation with an iconic name in horror. Which makes sense if you think about. With Halloween, Carpenter basically kick-started a genre for $300,000. I’d say that makes him an icon.