“It means something’s about to happen, something big…but then, something’s always about to happen.”

It’s a hoary, overused cliché to dub something “the best ____ no one has ever heard of, but Pontypool certainly fits the bill. It’s an underdog in every sense of the word: a Canadian horror film that began life as a radio play produced by the CBC (itself based on Tony Burgess‘s novel Pontypool Changes Everything), produced for a paltry $1.5 million, and making an even paltrier $32 thousand at the box office. It’s safe to say that no one has heard of this film – but those who have won’t stop talking about it, in a strange case of life imitating art. Pontypool has a gibberish title, a cast made up of unknown character actors, and a conceit that it is difficult to wrap one’s head around: it’s a zombie film where the infection is spread through words.

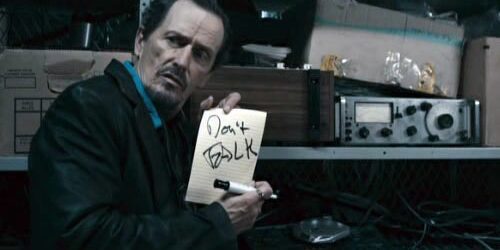

The film follows shock jock Grant Mazzy (Stephen McHattie, best known for small roles in Watchmen and A History of Violence, reprising his radio role) starting his early-morning shift at AM 660. On the way in to work, he sees a woman on the side of the road; when he asks “Who are you?” she fades away, and all we hear is the echo bouncing back: “Who are you?…Who are you?” which is a clever touch that really plays well on a rewatch. Setting a horror film at a radio station is like writing for this website: it’s a real gambit (sorry). You have to rely heavily on your actors to sell the gravity of situations that the viewer will only hear about. It could seem cheap and gimmicky, and if would have been, if Pontypool wasn’t so perfectly acted. Besides McHattie, the cast is rounded out by Lisa Houle and Georgina Reilly as Grant’s two producers, Sydney Briar and Laurel-Ann Drummond. With a single setting and bare-bones cast, director Bruce McDonad, a veteran of Queer as Folk, shows exactly how to make an effective horror film on a miniscule budget.

And here’s the thing: if Pontypool were just a zombie film, it would still be worth talking about. The execution really elevates the film, though. In one of the film’s most harrowing sequences, Grant talks to traffic reporter Ken Loney (Rich Roberts) as Ken describes the horrific events unfolding, which first were called a riot. “I’ve seen things today that are going to ruin the rest of my natural life,” Ken says; later he lets Grant hear babylike gurgling coming form the frame of a high school football player.

But it is Pontypool‘s originality that makes it so striking. It’s one of three zombie films I can think of in the last decade-plus that actually bothers to shake up the formula, the other two being 28 Days Later (fast zombies) and Shaun of the Dead (zombie comedy that’s actually funny). The virus is memetic in nature; it spreads through words. “Some words are infected,” it’s explained by Dr. Mendez (Hrant Alianak), at whose office the riots started. A warning, broadcast in French, admonishes against using the English language, and it is with this detail that Pontypool becomes ripe for cultural analysis.

The whole film is built around the power of language, and about how some words can irrevocably change the people who use them, even if in the film they’re pretty innocuous (“sample,” “missing,” “breathe”). There’s a clear message to take away from this, about the horrifically transformative power of hate speech, and it would be ham-fisted if it weren’t so fucking scary. When Laurel-Ann becomes infected, she babbles the word “missing” over and over, clamping her hand over her mouth futilely, before ramming herself against the window the sound booth, trying to get to Grant and Sydney inside. Reilly does dead-eyed determination with unsettling aplomb, and the whole sequence is so bleak and unsentimental that it’s almost a relief when she projective-vomits blood before dying.

But if that were all Pontypool had to say, it would be disappointingly nihilistic. McDonald – and Burgess, who also wrote the script – includes a terrific scene where Sydney gets infected with the word “kill,” and Grant has to figure out a way to make her un-learn the word. It ends with him frantically spitting words out, until he finds one that works: “Kill is kiss! Kill is kiss!” It might not be subtle, but it doesn’t have to be; McHattie and Houle are that good together.

Pontypool manages to feel nostalgic – the whole thing reads like a Stephen King story from the ’80s, specifically something out of Nightmares & Dreamscapes – and contemporary at the same time. Grant’s wardrobe is hopelessly out of date (with his leather coat, cowboy hat, and thin facial hair he looks like Time Out of Mind-era Bob Dylan), but he possesses the world-weariness and cynicism of the current day. It manages to balance hope and cynicism without betraying either. Pontypool is dark enough to end with the Canadian military bombing the radio station, but hopeful enough to believe in the restorative power of words as well. The gore is impressive, the music (by Claude Foisy) is haunting, and the events that unfold are terrifying, but what I’ll remember most about the film is: kill is kiss.

10/1: Dawn of the Dead (2004)

10/2: The Exorcist

10/3: Pontypool

10/4: Hocus Pocus

10/5: The Orphanage

10/6: Rosemary’s Baby

10/7: Alien

10/8: Scream series

10/9: Scream series

10/10: Cujo

10/11: The Cabin in the Woods

10/12: Pulse

10/13: The Babadook

10/14: Friday the 13th

10/15: The Last House on the Left (both versions)

10/16: The Thing (both versions)

10/17: Little Shop of Horros

10/18: Hush

10/19: Silent Hill

10/20: The Shining

10/21: Funny Games (2007)

10/22: Evil Dead series

10/23: Evil Dead series

10/24: The Mist

10/25: The Ninth Gate

10/26: The Fly

10/27: A Nightmare on Elm Street

10/28: The Nightmare Before Christmas

10/29: 28 Days Later/28 Weeks Later

10/30: It

10/31: Halloween